The Gulf War and Baudrillard

I seem to remember that at some point in the spring of 1991, David Letterman expressed the wish that CNN would bring back “that great Gulf War show.” And what a series it had been, for those not directly involved: a sound and light spectacular, real war carried live and as it happened.

The war was triggered by the invasion of Kuwait by its neighbor Iraq, led by Saddam Hussein, in August, 1990. Saddam took a number of European hostages, including a small boy who visibly, memorably, recoiled away from the dictator in a photo op. There was a long tense build-up, as military equipment and troops were moved into staging areas and as the United States and Great Britain went before the United Nations Security Council. Iraq was given a withdrawal deadline of January 15, 1991.

For the West, the war was about the liberation of the Kuwaiti people. It was about babies dumped out of Kuwaiti incubators, a story that turned out not to be true, and a curious, unnecessary invention in the midst of genuine war crimes (https://youtu.be/V6f2m4n1NVo). It was about laughing at spokesman Baghdad Bob for his alternative facts, and growing indignant when Saddam claimed that the Allies had bombed a “baby milk factory.” And above all, it was about saving the oil, even as the Kuwait oil fields were eventually set on fire by the retreating Iraqis.

The withdrawal deadline of January 15 came and went. On January 17, 1991, the evening broadcasts were interrupted by breaking news, in the days when “breaking news” caused people to gasp and go silent.

The French sent the third largest contingent of forces to the Gulf, under the name Opération Daguet; this brief subtitled video was made by the French Defense Department, and includes footage of the fighting, as well as of President François Mitterand (Socialist Party) who supported the war.

In his speech to the nation after the war had started, Mitterand justified France’s participation by the need to uphold the United Nations. He acknowledged that France itself was not threatened, and that the 12,000 French troops on the ground had after all chosen the military profession (a curious comment, perhaps meant for those who might worry about them). But Saddam Hussein had violated the United Nations resolution and ignored the ultimatum: “You must be certain of this,” he concluded; “to protect [international] law in the Gulf and the Middle East, as far away as it seems on maps, is to protect our own nation”(Le Monde, January 18, 1991). This justification had a distinct echo, intended or not, of Neville Chamberlain’s remarks on Czechoslovakia in 1938, of “a quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing.” This time the West would not fail.

But the justification came off as rather strained, and Le Monde was perhaps appropriately cynical. “It’s 5 am. Paris is waking up, and it’s war. The news is spreading in the streets of the capital with the first cars [of the morning] and the last taxis of the night. It surprises the night owls of the Left Bank, takes hold of the suburbanites as they leap on the train, animates the discussions in cafés. . . . There are the euphoriques (“It was time!”), the fatalists (“It had to happen some day”), the militants (“I was against it, I remain against it . . .sic)”, and the indifferent (“I’m going to be late for work!”) (Le Monde, January 18, 1991). Mitterand was right, however, about one thing: the French indeed knew what war was. And this wasn’t it.

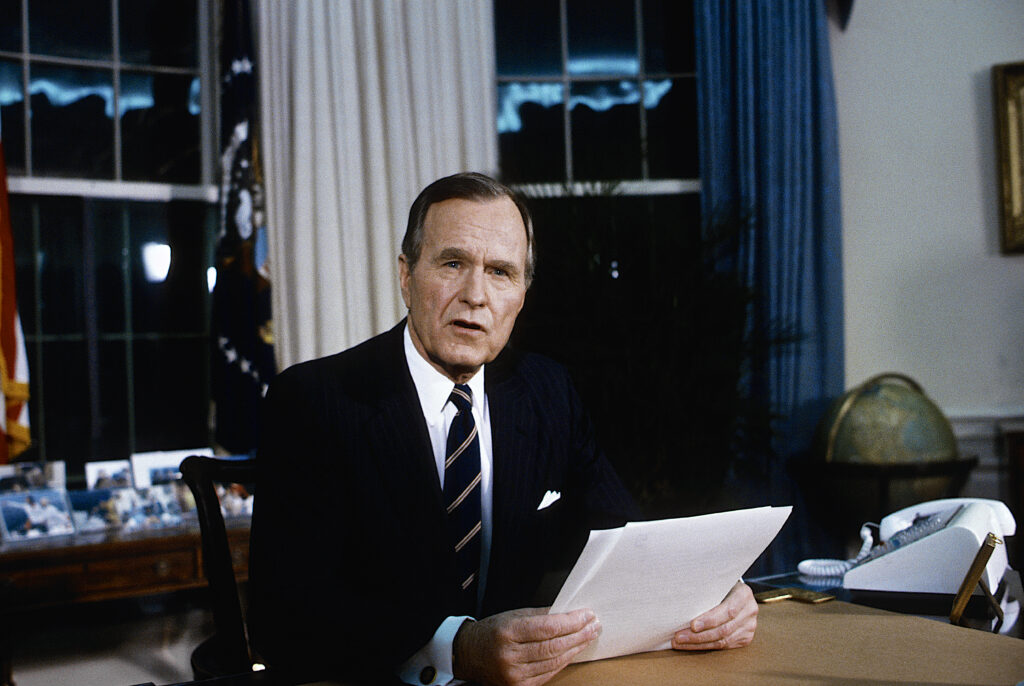

The war lasted a little over a month; President George W. Bush announced the suspension of hostilities on February 27, 1991.

Saddam Hussein was left in power, and in spite of the surveillance operation known as “Southern Watch” (the header photo, above), Saddam continued to drain the wetlands (leaving behind a desert, driving out the Shi’ite Muslims who lived in the areas), and felt free, over the next twelve years, to terrorize and kill his political enemies, including the Kurds. Saddam was not removed from power until after Al Qaeda attacked the United States on 9/11. (It did not make sense as a reaction to 9/11, then or now.) In 2003, French President Jacques Chirac (UMP, or the Conservative Party) declined to have France participate in the coalition, explaining himself in an interview with Christiane Amanpour (who told him of the resentment in the United States, including the Republican insistence on “Freedom Fries” in their Congressional cafeteria). Chirac responds in his typically elegant fashion, revealing some embarrassing truths:

What of his personal relationship with Saddam, the photo of the two of them side by side, smiling, during Saddam’s visit to France? “I did indeed meet President Saddam Hussein when he was vice-president in the mid-70s, but never since. But in those days, everybody had excellent relations with Saddam Hussein and with his party. It was seen as progressive. Everybody had contacts with them, including some important figures of the current US administration, had contacts with Saddam Hussein as late as 1983. But not me (5:50).” He denies several other allegations, then is asked (10:40) about his statement that the presence of the United States and British coalition forces had forced Saddam Hussein to comply with the international WMD inspections. He reiterates his assertion: “I would say that the Americans have already won, and they haven’t fired a single bullet” (10:20). Chirac is speaking as a friend, he says, trying to warn another friend that he is about to make a mistake.

(In spite of the nonparticipation of the French in the Iraq War, a number of young French Muslims were radicalized by it, including Chérif and Saïd Kouachi, who would massacre the journalists of Charlie Hebdo in 2015. The New York Times, January 17, 2015).

(Back to the original Gulf War in 1991. They often merge together, given that they share the same protagonist Saddam Hussein. But back to 1991.)

Shortly before the beginning of hostilities, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard wrote a famous essay, published in Libération, titled, “The Gulf War will not take place.” After the war began, he published a second essay, “The Gulf War: Is it really taking place?”, and finally a third essay after the end of the war. All three were published under the name of the third essay, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (1991).

Baudrillard wrote about the hyperreal, the simulacra that are more real than real. Do I understand Baudrillard? Not in the slightest.

But perhaps the simplest way into Baudrillard’s interpretation of reality as applied to the Gulf War is through film. Baudrillard was not suggesting that the Gulf War was a Capricorn One scenario, in which a fake moon landing is filmed in order to conceal the fatally flawed space ship (Baudrillard, Gulf War, p. 61). Instead The Matrix was generally agreed to be the most relevant film of Baudrillardism, and was inspired by his work; a copy of his Simulacra and Simulation appears in the film (NPR, March 7, 2007). The Matrix ends (spoiler alert) with the revelation of the world that exists behind the matrix: wasted human bodies in pods, wired up to simulated images that give them the illusion of fully existing in a real world. Baudrillard was said to be conflicted about the film, and understandably so: he was speculating about the nature of reality, not bodies in pods.

In The Gulf War, his arguments appear to be both prosaic (it was not a real war) and something Baudrillardian, perhaps best summed up as the non-transparency of total transparency (my words). A clue to his thinking in regard to the first point, that it was not a real war, can be found in the comments from Iraqis in Baghdad in the ABC report, as they grimly prepared for a prolonged contest–perhaps like the eight long years of the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s–that they were determined to win. One young man, hoping that the war would not occur, urged that war would be “devastating to both sides.” But of course it was not. It was devastating to Iraq. It was devastating to individual coalition soldiers and their families, some of whom suffered longterm debilitating injuries.

It was not devastating, at least not immediately so, to the United States or to any of the coalition partners. Baudrillard, in fact, mocks the frenetic news coverage on February 22, divided between bulletins of the beginning of the land offensive in Iraq and (treated as equally devastating) the massive traffic jam as thousands of Frenchmen made their way to the ski slopes of Courchevel (Baudrillard, pp. 75-76).

Baudrillard’s argument, then, is that the Gulf War was not a war, but rather an asymmetrical display of advanced military technology. The Iraqis were never in the game at all. And though he grossly underestimated Iraqi casualties, both military and civilian, Baudrillard nevertheless warned of the dangerous contempt shown to the enemy in such a war:

“There is undoubtedly a political error here, in so far as it is acceptable to be defeated but not to be put out of action. In this manner, the Americans inflict a particular insult by not making war on the other side but simply eliminating him, the same as one would by not bargaining over the price of an object and thereby refusing any personal relationship with the vendor. The one whose price you accept without discussion despises you. The one whom you disarm without seeing is insulted and must be avenged” (casualties https://www.forces.net/news/remembering-gulf-war-key-facts-figures, March 7, 2017; Baudrillard, p. 40).

Finally, and above all, the war was a non-event because Saddam was left in place in Iraq: “The same Americans who, after having dumped hundreds of thousands of tonnes of bombs, today claim to abstain from ‘intervening in the internal affairs of a State” (Baudrillard, Gulf War, p. 79).

Now the Baudrillardian meaning.

In L’illusion de la fin, Baudrillard suggests a version of the end of history, meaning the end of a history accompanied by a metanarrative or overarching story that makes sense of it: the late 1980s/early 90s clearly marked the end of the narrative of socialism (Baudrillard, l’illusion, pp. 39-40). With the collapse of the USSR and the independence of their former satellites, the inevitability of the socialist revolution, so much a part of its strength, was gone, and socialism was left searching for an identity: in France that identity finally shattered into fragments with the election of 2017.

So History, says Baudrillard, has ceased to be about these themes, and is now about “an accumulation of proofs” (Baudrillard, Gulf War, p. 39), which mean nothing in themselves. The massive filming of the Gulf War, the “accumulation” of uncontextualized video clips, of interviews, of cockpit simulations that flattened out the landscape and eliminated the people, was instead a boon for “video-zombies” who would collect the cassettes (now he would say, plant themselves on youtube) and “who will never cease reconstituting the event” (Baudrillard, Gulf War, p. 47).

Add to the images the endless “pontificating” and commentary by would-be experts: “Fortunately, no one will hold this expert or general or that intellectual for hire to account for the idiocies or absurdities proffered the day before, since this will be erased by those of the following day. In this manner, everyone is amnestied by the ultra-rapid succession of phony events and phony discourses” (Baudrillard, Gulf War, p. 51). The multiple images were edited and packaged into discrete events for the evening news (or the 24-hour news cycle) and the narrative was crowd-created into a sort of conventional wisdom about what was happening. Baudrillard kept hoping, he said in 1991, that “some event or other should overwhelm the information instead of the information inventing the event and commenting artificially upon it” (Baudrillard, p. 48). We saw more images of this war than we had ever seen of any war before; and we knew less.

(Though France stayed out of the 2003 Iraq War, it nevertheless would radicalize a number of young French Muslims, including Saïd and Chérif Kouachi, who would massacre the editorial staff of Charlie Hebdo on January 7, 2015).

Philippe Lançon was a young freelance reporter in Baghdad during the first Gulf War. He was staying at the Al Rashid Hotel, as were all the reporters and “invited guests” of Saddam, the latter including Louis Farakkan and Daniel Ortega (Lançon was disappointed in him) and especially the “North American pacifists, delighted to play their role as useful idiots and human shields” (Lançon, Disturbance, p. 35). Nearly a quarter century later, on January 7, 2015, looking at the worn Persian rug in his apartment, he remembered that he had purchased it from a vendor in the last days before the Gulf War began, as the embassies closed up and the streets became deserted, inhabited only by those as eager as himself. “Nothing is more flattering or more exciting than finding oneself in a place that others have deserted, in the eye that waiting hollows out at the center of the hurricane. We were young, uneasy, and hungry. History seemed to be our adventure and our property” (Lançon, p. 34).

But he had left the city on the last plane to Amman, had lost the exclusive, and had decided that he was not cut out to be a wartime journalist. He became, instead, a distinguished writer and literary and cultural critic. On the morning of January 7, 2015, he was annoyed with Michel Houllebecq because of his recent novel Soumission (a satire, or fantasy, on the election of a Muslim to the presidency of France, and his remolding of the country into an Islamic state); and because of the author’s television interview (Lançon, pp. 30-31).

In the midst of his irritation he was trying to decide whether he should go to his office at the newspaper Libération, or whether he should stop by the editorial meeting at the small, failing weekly where he also contributed.

For whatever reason, he decided to stop by Charlie Hebdo first.

He would spend the next year enduring the multiple surgeries necessary to reconstruct the lower half of his face.

==============================

Baudrillard, Jean. The Gulf War did not take place. Translated and with an introduction by Paul Patton. Sydney, Australia: Power Publications, 1995.

Baudrillard, Jean. L’illusion de la fin. Paris: Galilée, 1992

Lançon, Philippe. Disturbance. Translated by Steven Rendall. Paris: Europa Editions, 2019.

Header image by Shutterstock.com.