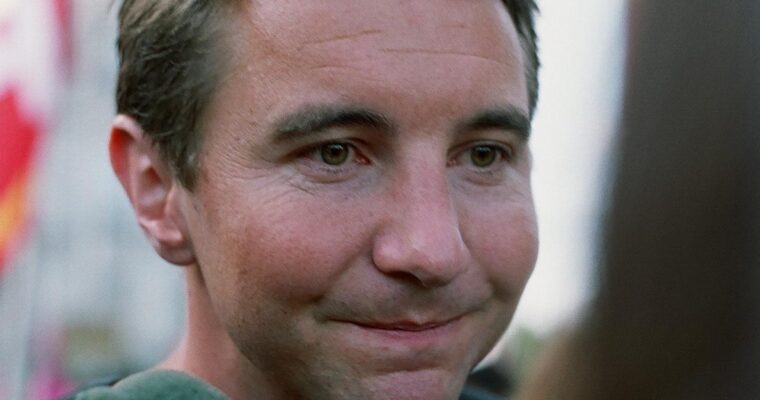

Pierre Bérégovoy was President François Mitterand’s Prime Minister from April 1992 to March 1993. He had been a party activist for decades, and was present at the Congrès d’Épinay in 1971, when Mitterrand brought together the different elements of the Left to found the current Socialist Party. After Mitterand’s election in 1981, Bérégovoy had served in many positions in his two seven-year terms, including the direction of his second campaign, in 1988, culminating in his appointment as prime minister. His most important assignment as Prime Minister was to secure a majority in the Legislative elections in 1993; instead the Socialists suffered an historic defeat. Bérégovoy won his own election, in the Nièvre department, but he immediately resigned as prime minister.

He also served, as many deputies did at that time, as a mayor. His city was Nevers, a town of about 26,000 in central France. He came to Nevers on the morning of April 30, 1993, and spent the rest of the day in meetings on employment, agriculture, a new hospital. In the late afternoon he invited some local officials for drinks on the terrace of a restaurant on the banks of the Loire River. “We should do this more often,” he said, as they departed. He had dinner with his family. The next day was May 1, 1993, or May Day. He told his driver to pick him up for the festivities at 10:30 am.[1]

There are two things that everyone in France knows about Pierre Bérégovoy.

First, he was a worker–not just a workers’ son, but an actual worker himself, who had to leave school at 16 in 1941 in the midst of war. He became a cheminot, or railway worker, and as such was a part of the famous Résistance of the rails, in the dangerous role of passing messages about cargos, troop movements, and timetables. After the war he obtained a position in the Gaz de France company, where he received managerial training; aside from that, he had no further education after leaving high school, and biographies generally refer to him as an autodidact. His passion was politics, and his union membership and local activism, with endless nights in smoke-filled rooms, arguing over policy and strategy, carried him into the Socialist Party and into the dizzying heights of power.

Bérégovoy’s father, Adrien, was a Ukrainian soldier in the Tsar’s army who had fled, penniless, to refuge in France. He got work in a factory. He married his landlady’s daughter. Dominique Labarrière, who has written about Bérégovoy, compares his father to the writer Annie Ernaux’s father in A Man’s Place–a working class man who dreamed of property and independence which came in the form of a small grocery/café that catered to the poor and ran on credit. Ernaux’s mother ran the store and her father took a job in a nearby factory to keep them–to keep the store–afloat. Both worked constantly. Bérégovoy’s parents had two grocery/cafés, interrupted by a failed attempt at farming, both run by his mother Irène, who cooked some 30 lunches every day while his father held a factory job. For a time, Bérégovoy had to live with his grandmother because his parents could not support him. L’Homme de la Rive, which includes an assemblage of family photos and documents, has several pictures of Adrien. In one, he is standing proudly in front of the aged and broken wooden door of the old building that housed his grocery; in another, Adrien is standing, his face serious, beside his seated wife on their wedding day. She is in her simple bridal gown; she has a hint of a smile.

The other thing that everyone knows about Bérégovoy is that he committed suicide on May 1, 1993, in his home district of Nevers, only two months after his departure from office. He had asked his guard and chauffeur to stop the car and let him walk for awhile in the woods. He shot himself in the head with his bodyguard’s handgun, which he had managed to take from the car. He survived for a few hours, and died in the helicopter taking him to Paris.

Why did he do it? There were a number of answers put forward. He was depressed about the elections. He had resigned as prime minister, thus implicitly taking all of the blame for the loss. A friend in Nevers, interviewed after his death, stated that he had seemed disappointed by the poor turnout for May Day in Nevers[2]–not a reason, of course, but perhaps an additional indication, to him, of failure. He had been accused by Le Canard enchaîné, a rather odious “satirical” weekly, of corruption: in 1986 he had received an interest-free loan of 1 million francs, or 150,000 euros, from an old friend (of his, and of Mitterand’s), Roger-Patrice Pelat, for the purchase of a residence in Paris, obviously not a lavish one. Pelat later became implicated in an insider trading scandal. Bérégovoy was not in ministerial office at the time of the loan, nor likely to be (the most recent legislative elections had returned a conservative majority, and Jacques Chirac was Mitterand’s prime minister). Moreover, the loan was a matter of public record, having been filed with a notary and in the court records–but it was a blunder, and a big one; and there would likely have been an investigation, in the press if nowhere else, that would have subjected him to further scrutiny.[3]

Labarrière wishes for him more insouciance, a more strategic use of his working class background rather than shame and feelings of inadequacy. And why did the family change the spelling of its name to a French version, and why did he maintain that? Why not leave a modified Ukrainian form of his name and have around himself the aura of an émigré past, a never-expressed but never-denied hint of high birth in imperial Russia? And, when asked by a rude interviewer what qualifications he had to be Minister of the Economy, why did he become defensive? Visibly upset, he had responded, “If I were an énarque (graduate of the ENA) would you ask me that question?” Said Labarrière, “It’s all in tone and attitude. Accompanied by a smile, a spark of malice, this response would have been a winning blow. Tense as it was, defensive and not gaily impertinent, it appeared as an acknowledgement of weakness,” as “the inferiority complex that he had always dragged with him.”[4]

Of course there were conspiracy theories, rumors that some had heard a second shot, his missing daily planner which would have shown his appointments, perhaps with the assassin. None of these came to anything. The current assumption is that he was depressed at a series of perceived losses, depressed at the unlikelihood that he would ever be able to regain his stature and reputation, a more enhanced version of the imposter syndrome he had always carried with him–and pulled the trigger.

====================================

Header Image: By Amalricc – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32459213

[1] Information from Dominique Labarrière, La Mort de Pierre Bérégovoy (Paris: La Table ronde, 2013), pp. 19-23. The population for Nevers is from INSEE.

[2] https://youtu.be/AvqvUd0e9EA, News report of his suicide.

[3] Labarrière, La Mort, pp. 68-72.

[4] Labarrière, La Mort, p. 59.

See also Jules Roda, Philippe Roc, Pierre Bérégovoy: L’Homme de la Rive (Rouen: Éditions 319, 2005).