La Bérézina

Review of:

Marylou Magal, La BéréZina: Éric Zemmour, Autopsie d’une déroute électorale. Paris: Éditions du Rocher, 2022.

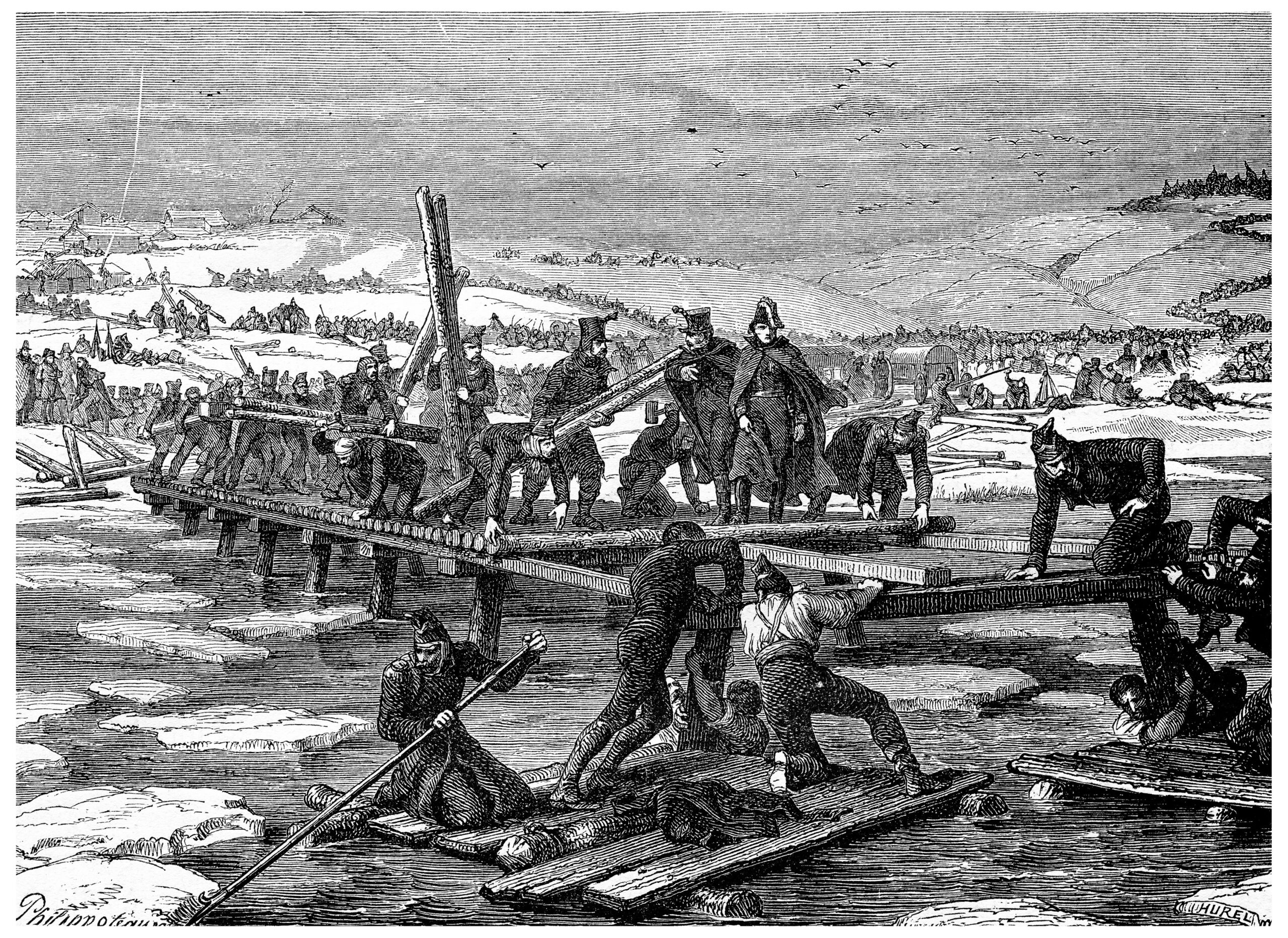

The reference to someone’s defeat as their “Waterloo” is, in France. superseded by the term “Bérézina.” It refers to the horrific battle in late November, 1812, during Napoleon’s retreat from Russia with perhaps as many as 50,000 armed men, and tens of thousands of “stragglers,” those who had lost their weapons or were simply what was left of the support staff necessary to the 600,000-man army that no longer existed. The Russians destroyed the bridges over the Berezina River in Belarus, a tributary of the Dnipro River in Ukraine. The French found some shallows; the engineers, led by General Jean Eblé, built two bridges, one for personnel and one that could also carry heavy equipment, which collapsed about halfway through. Desperate diversionary attacks bought the necessary time for construction and evacuation. The crossings began on the afternoon of November 26, when one bridge was finished; Napoleon gave orders to blow the bridges in the early morning of November 29. Many of the stragglers remained behind, too cold or exhausted to move.

Éric Zemmour’s campaign wasn’t quite as bad as that. But it wasn’t great. The worst problem, as Marylou Magal indicates, was Zemmour himself, who had neither the depth nor the political acumen to win.

The rise and fall of French presidential candidate Éric Zemmour, the television personality who wanted to be another Trump, has already received one of the best day-to-day analyses it will likely get from Magal, a political reporter for Le Figaro. She presents Zemmour as an intellectual bomb thrower by trade, both in the written word and as a commentator on the conservative CNews. At the first hint that he might get in the presidential race, in October 2021, his popularity soared, taking him a few points beyond Marine Le Pen; analysts began to poll about his presence in a hypothetical second round against Emmanuel Macron (p.33). But the very qualities that had initially attracted a hard-core base soon began to cause doubts. He at first seemed a possibility for the educated bourgeoisie, in large part because of his erudition: they were impressed by his facility with language, his apparently deep knowledge of history (leading a group of major historians to publish a small book pinpointing how he got history wrong).[1]

Beyond all that, he has been involved in a number of controversies by pushing the boundaries and occasionally going over them, in terms of what is legally liable, and as a result has been convicted several times (2010, 2018, 2022) for incitement to racial or religious hatred. The last verdict, rendered in mid-January 2022 during the campaign (admittedly it was for a remark made in 2020) was for referring to unaccompanied minor immigrants as “thieves, murderers, and rapists.” (He did not even add that some were very fine people.) Zemmour condemned his conviction for this remark as “ideological and stupid.”[2]. Still, it raised the question of temperament and self-control.

As Magal shows, Zemmour’s popularity was peaking and had even started to decline before he declared for the presidency in November 2021, though he perhaps revived a bit on December 5, when he announced the founding of his own political party, Reconqûete. His biggest disappointment was his failure, at least at first, to win over “heavyweights” from Les Républicains (LR) especially; there were relatively few of those, but a good many National Rally (RN) members, who brought along with them the baggage that kept people from voting for the National Rally in the first place. They wanted Laurent Wauquiez, president of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region and a former Chair of the LRs; they dreamed of Éric Ciotti, current chair of the LRs, both on the far right of that party. They weren’t going to get them, even though Ciotti said he would vote for Zemmour over Macron in a hypothetical second round (p. 52). Perhaps Zemmour’s biggest convert was Senator Stéphane Ravier from Marseille, a decidedly mixed bag, a frontiste who had originally joined the FN under Jean-Marie Le Pen and was devoted to him and to Marion Maréchal, Le Pen’s granddaughter.[3]

Moreover, those he attracted were not altogether in harmony. Jean-Frédéric Poisson, one of the earliest to rally, was a social conservative who had come to prominence in 2013 as an opponent of the same-sex marriage law; he was strongly Catholic and opposed to abortion as well. He had founded his own political party, Via,la Voie du peuple, and was planning to run for president himself before joining Zemmour, and he remained a stalwart surrogate to the end. Poisson and some of the other “early adopters,” however, were disturbed by the subsequent visibility of Damien Rieu and several others from Génération Identitaire, a group dissolved by Minister of the Interior Gerard Darmanin in March 2021 for incitement to discriminate on the basis of origin.[4] Some of these Identitaire youth had been members of the RN, but as Magal notes, they had been mostly kept on the fringes, selected as “parliamentary assistants” to MEPs, though Rieu was able to run for Péronne (Somme), in the departmental elections in 2021 (he lost). And Jacline Mouraud, one of the early figures of the Gilets Jaunes who hoped to bring working class issues to this very elite group, felt disrespected by them; her book, Jacline Qui? (Jacline Who?) is due out on March 2.

Magal gives a leading role to Sarah Knafo, generally only described as Zemmour’s “companion,” who burst into public consciousness with a Paris Match cover that showed them vacationing on the Riviera. (Zemmour, born 1958, has been married since 1982 and has three children; Knafo was born in 1993).

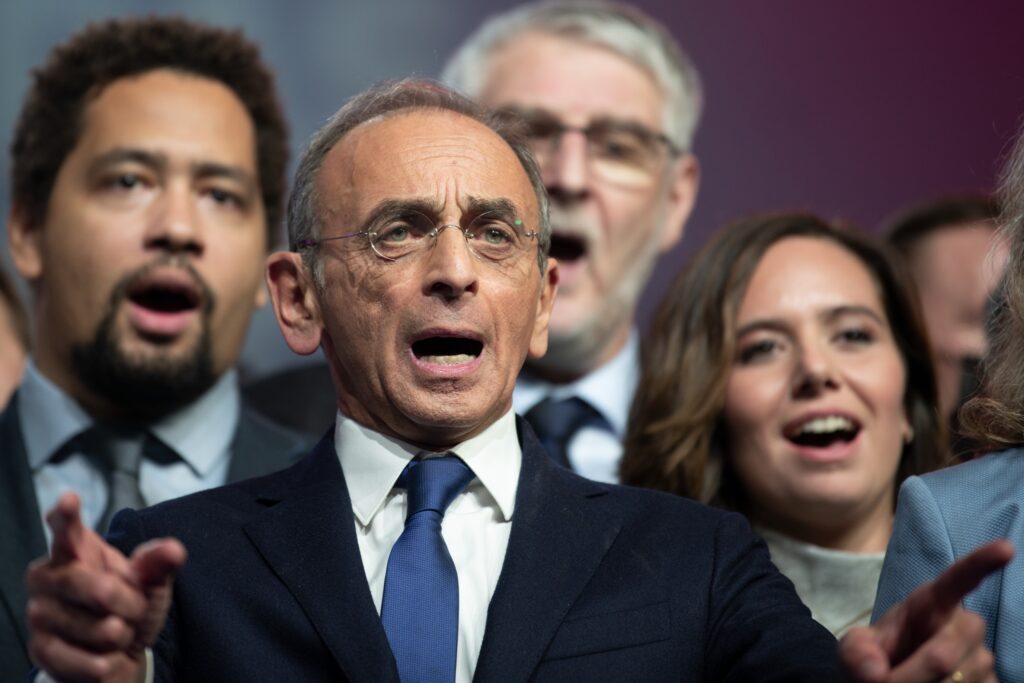

Éric Zemmour, center; Sarah Knafo, the only woman in the picture.

Magal places Knafo, a right-wing activist, a graduate of Sciences Po and ÉNA, clearly at the center of the campaign and in fact as its true leader, as someone who conceptualized the role that Zemmour was, in the end, unable to play. Knafo saw him as embodying the union of the Right–the LR, the RN, and the “droits hors les murs” (the “rightwingers outside the walls,” that is, unable to fulfill their precise needs in either of the other two parties), bringing together its best themes–the economic (neo)liberalism of the LRs, joined with the focus on immigration and nationality of the RNs (thus without Marine’s crude economic populism). Knafo expected Zemmour’s candidacy to create a new party, or movement, that would leave the two other parties in the dustbin of history. Zemmour did not quite fill this role of unifier, unable to restrain his impulses to be a bomb thrower, to bloviate without contradiction as he had for so many years on CNews. This is not, as Magal notes, a quality that one wants in a president.

He held a series of packed rallies that suggested, in contrast to the polls, that his movement was going to overwhelm the elections. Those around him, however, were beginning to wonder about the frenzied round of events, with a “fanaticized” electoral base that came to each one; according to one conservative commentator, “All his voters are in the hall, there are no reserves” (p. 83) On March 6, 2022, Marion Maréchal formally endorsed him at a rally in Toulon.[5]. Her adherence had been rumored since January, at least, and she joined when the campaign was ebbing. Marine Le Pen had joked that “they think she’s the Holy Grail”; as Magal described it, the remark was made “on the margins” of a press conference Le Pen had just held, thus neither part of her formal responses–nor off the record (p. 115).[5]

Nor was Zemmour able to convince people that he “got” French voters’ concerns about the cost of living, preferring instead to speak in grandiose terms about the survival of French civilization threatened by Islam. Knafo arranged a speech on economic matters which laid out his program: tax cuts; cuts in withholding taxes; no taxation on overtime. All to be financed by withholding social services from foreign immigrants (p. 126). He made a couple of mistakes in the last few weeks of the campaign, including his insistence that France should not admit Ukrainians fleeing the Russian assault, because he believed that there should be an end to all immigration (p. 137). In late March, in a television appearance, he called for a “Minister of Re-migration,” popular with Identitaires but not with the French people as a whole (p. 140).

By the time of his Trocadero speech on March 21, something of a tradition among losing candidates on the Right (Sarkosy, 2012; Fillon, 2017), the inner circle was talking confidently about the “hidden vote,” invisible to the pollsters, that would propel him into the second round on Election Day. That was for the followers; none of the leaders believed in votes that were somehow flying below the radar (p. 151).

He came in 4th, with about 7% of the vote.

===========================================

Images by Shutterstock.com

[1] Collectif, Zemmour contre l’histoire, Tracts Gallimard, 2022. The book has a number of short titles based on statements by Zemmour, such as “Vichy did not save French Jews,” “The Nazis were not the heirs of the Enlightenment,” “Dreyfus was not Guilty.”

[2]”Election présidentielle 2022,” Le Monde, January 17, 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/election-presidentielle-2022/article/2022/01/17/election-presidentielle-2022-emmanuel-macron-vante-l-attractivite-de-la-france-eric-zemmour-critique-la-justice-apres-sa-condamnation-le-recap-politique-du-jour_6109846_6059010.html

[4] See an earlier post, https://jharsin.colgate.domains/blog/uncategorized/generation-identitaire/).

[5] See an earlier post. https://jharsin.colgate.domains/blog/uncategorized/campaign-chronicles-the-coming-of-marion/