Summer, the Sixties, and Françoise Dorléac, 1942-1967

In 1964, two movies were among those in competition at the Cannes Film Festival: The Soft Skin, directed by François Truffaut; and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, directed by Jacques Demy, which took the prize. The first starred Françoise Dorléac. The second starred Catherine Deneuve. They were sisters; Françoise was about 18 months older, and she used her father’s name, while Catherine used her mother’s maiden name. Both were beautiful, but Françoise was the pretty one.

They made one film together, Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967) directed by Jacques Demy, in which they played twin sisters. In this rehearsal scene, they seem to have borrowed the choreography of Little Edie in Grey Gardens; I can’t unsee it.

Françoise Dorléac was killed in a single-car fiery crash on June 26, 1967. She was speeding away from St.-Tropez, where she had been visiting her sister, to get to the Nice airport in time to catch her plane. She was twenty-five. She missed everything from then to now.

In her more than fifty years as an actor (Catherine Deneuve, Imdb), Catherine Deneuve has become an icon of French cinema, fearless about taking public stands on controversial issues, and not always on the most popular side. In 1971 she was one of the 343 prominent women, including Simone de Beauvoir and director Agnès Varda, who signed a declaration that she had had an abortion. In 1975, after much agitation and negotiation, the law permitting abortion up to ten weeks was passed in France (Ozy.com, March 2, 2017).

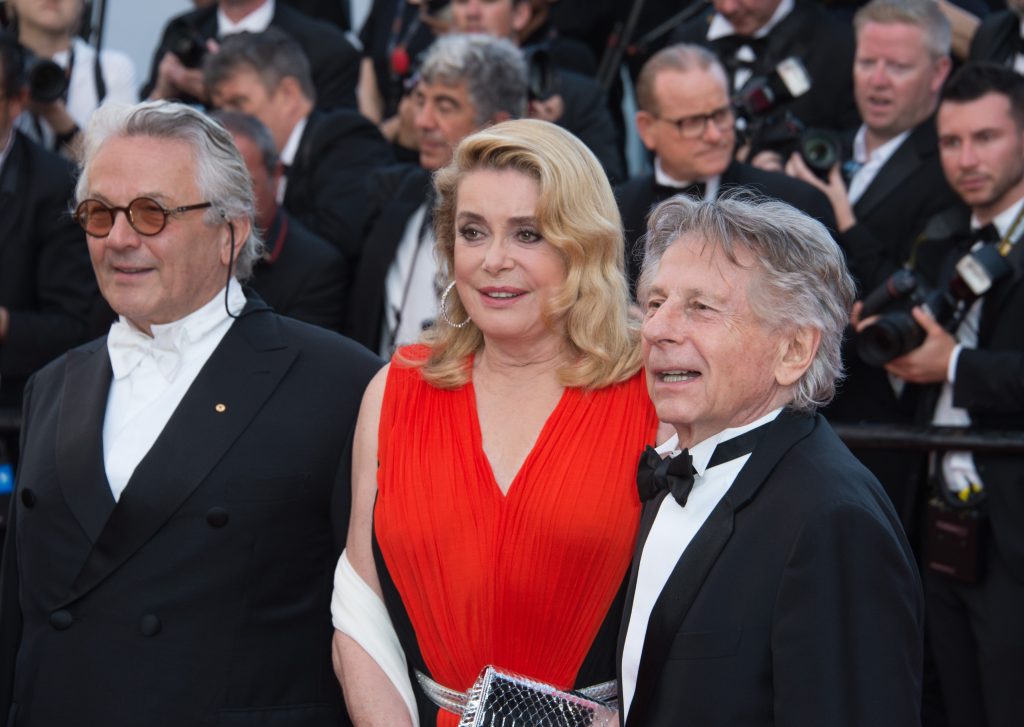

In early 2018, in a less happy moment, Deneuve was one of 100 women, and the most famous of them, who signed a petition against the excesses of #metoo–or as it was then hashtagged in France, #balancetonporc (Deadline.com, January 9, 2017). The letter did not express a particularly coherent argument–it conflated assault, touching, and “importuning” (as did the early #metoo movement in some cases–remember babe.net?) but it sounded distinctly old-fashioned, too much of a vive l’amour, French-maid-being-chased-by-the-employer sort of worldview. When some of her co-signers began to say outrageous things, she apologized publicly (The Guardian, January 15, 2018.). In 2017 she was photographed on the red carpet at Cannes with Roman Polanski (arrested for the rape of a minor, he had pled guilty to a lesser charge); but she had made Repulsion with Polanski in 1965, and Polanski had directed her sister in Cul-de-sac in 1966. (And she is now in her 70s, and can do whatever she pleases.)

In 2011, speaking of her sister’s death an astonishing 44 years earlier, Deneuve stated that “when one has lived through such a profound grief at a young age, it never leaves you. Never. . . . We live with our dead, not as much as with the living, fortunately, but all the same they are there. . . Yes, I ask myself what sort of actress she would be today, what she would be like physically, if she would have continued in films or adopted the theater as her anchor. I ask myself also if our relationship would have remained the same” (Purepeople.com; photos as well). In 2016 Catherine Deneuve described her sister’s death as “the most painful thing I have ever lived through” (Marie Claire, 2016). And there was no deus ex machina to save either one of them.

I first encountered Françoise Dorléac long after her death, and in a movie that was not her best, though she was the best part of it. I remember the film as being better than it looks in the trailer, though I had forgotten the unfortunate James Mason and Robert Morley appearances.

Dorléac was not a woman of the twelfth century but of the 1960s–mod, with-it, daring, playful, a girl of eternal summer (for this was the time when women were girls). She is shown in this short film engaging in typical Saint-Tropez activities, not always gracefully: she nearly falls off her bike, and I think that the chihuahua gets into her drink:

Her best and happiest movie, in many ways, is the irrepressible That Man from Rio (1964) directed by Philippe de Broca. Jean-Paul Belmondo plays Adrien, in love with Dorléac as Agnès, the daughter of a professor of archaeology or some such, now deceased. It is unclear, by the way, why the film is named That Man from Rio; there is no such character. Jean-Paul Belmondo goes to Rio in the course of the film, but he’s French, and anyway he soon leaves for Brasilia. Aside from that puzzle, this film is an all-out physical comedy that is genuinely funny and paced at the speed of sound; it is clearly one of the inspirations behind Raiders of the Lost Ark, and does some things even better.

The story begins in the Musée de l’homme in Paris, where a clay statue of extraordinary power is stolen by an unknown person. The statue is one of three: Agnès’ late father had one, and buried it in Brazil, his colleague and fellow professor had another, and the wealthy Brazilian businessman who financed the expedition had a third (he’s not from Rio either). If you bring the statues together at a certain place in the wilds of the Amazon interior, something will happen and you’ll get the gold. Whoever stole the first statue is probably heading for Brazil. Agnès is kidnapped for her knowledge of the second statue’s location, Adrien follows her in full rescue mode, and in the course of the adventure they see–we all see–Brasilia under construction, which makes for fascinating, never-to-be replicated location shots.

Which is not to say that the film doesn’t have problems. As the heroine, Dorléac has more energy and agency than the Princess Bride, for example, but she gets picked up and moved more than seems strictly necessary; she is also scatterbrained. The Black child, “Sir Winston,” is excessively precocious, apparently an orphan, and makes his living as a shoeshine boy. He saves the lives of Adrien and Agnès, he gives them a place to stay, he gets them a car, and they dump him without a second thought. But Winston is not alone in this fate: Brazil and its people exist merely as a gorgeous backdrop for the bumbling quest of the Europeans. The final shot is surely one of the most blithely cruel moments in film.

But I like the movie–and it’s teachable, as a time in cinema and society when such insouciance about other peoples and places was neither ironic nor even recognized.

Nostalgia for the immediate post-colonial world of the 60s? Maybe. (But only if you can forget the Algerian War just ended for Algeria and France, the Vietnam War still continuing for Vietnam and the United States.) For the 60s before the riots of ’68? Possibly. For the time when the Promenade des Anglais in Nice was just a stunning beachside street, rather than the location of the 2016 truck attack? Most certainly.

This short film, featuring Brigitte Bardot, takes us to the Riviera in the company of old (or rather new) cars and boats, pop stars, monokinis. It reveals a time and a place that is no longer imaginable–ruthless segregation, privileged heedlessness, a belief that things would go on as they always had, forever and ever.

In May, 1965, Dorléac performed “Mario, j’ai mal”; she had just under two years to live.

The Paris student riots and factory worker strikes occurred throughout May and June 1968. Dorléac had been dead for nearly a year when they began.

And by the way: De Gaulle won the referendum. Workers went back to work. The students were kicked out of the Sorbonne. And the world had changed.

==============================================

Header image by Shutterstock.com.