The Regionals in Hauts-de-France and the Presidential Election

The région of Hauts-de-France came into existence in 2016, as Picardy was added to the previous Nord-Pas-de-Calais region. It is the northernmost part of the country, bordering Belgium and the English Channel, and includes the cities of Lille (the site of the Prefecture), Dunkirk, Amiens, and Calais. Dunkirk was the site of the heroic evacuation of troops in 1940, over 100,000 of them French, who became the core of General Charles De Gaulle’s military force. Calais, the French end of the Channel Tunnel, has become the place where migrants gather in the so-called “Calais Jungle” tent city, most of them waiting for a chance to get to England. It is periodically cleared out by the French government.

Amiens, the hometown of President Emmanuel Macron, was the place of a confrontation of sorts between Macron, who had come to discuss job losses at the Whirlpool plant, which was closing; and Marine Le Pen, who made a surprise photo-bomb visit to the striking workers, even as Macron was talking to the city government and union officials. The event was one of the key moments in the “between two rounds” coverage of the presidential campaign, when Macron and Le Pen had emerged as numbers one and two in the first round of the presidential elections.

Amiens was also a signal of Le Pen’s ongoing attempt to capture the working class vote, forgotten (as she said) by the elites in Paris, of whom Macron is inescapably one.

The Hauts-de-France region was beaten up in both world wars. It has since been ravaged by factory and mine closings and the loss of much of its industrial base, as global giants close plants and move their jobs elsewhere. The Nord-Pas-de-Calais region was a traditional Socialist Party stronghold, as was Picardy. But in 2014 the town of Hénin-Beaumont, population just over 26,000, elected a top official of the National Front party, Steeve Briois, as its mayor; in March 2020 he was re-elected, in the first round, with 73.95% of the vote. The raw numbers were less impressive: his winning percentage was composed of 5,750 votes; of those eligible, 55.38% of the population did not vote.(1) Nevertheless, in 2015 Marine Le Pen named Hénin-Beaumont as a great “turning point,” [virage] for her party’s strength beyond its stronghold in the south. It was to be a demonstration, as well, of the National Front’s ability to govern efficiently. Hénin-Beaumont would show that the National Front (changed to National Rally in 2018) was a normal political party, and that it had replaced the Socialists and Les Républicains as the alternative to Macronism. Briois, interviewed in 2014 the day after his victory, stated that the strong showing of the FN was not a “protest” vote, but rather a vote “of adhesion” in favor of the FN program on matters of “security, immigration, employment, Europe [European Union], globalization”(2)–the same issues the RN runs on today, with the climate, then and now, very much omitted. Sébastien Chenu, the head of the list in Hauts-de-France, has even opined that the environmental transition in general, and windmills in particular, are “frauds” against the people of the countryside. (2bis)

Seven candidates are running as head of the list in the Regionals, a position that also means that they will, if their list wins, be elected as President of the Regional Council.* The elections will be held on June 20 and June 27, postponed for a few months because of Covid.

The debate on June 2, 2021, which included all seven of those running, began with an interesting and surprisingly revealing moment. Each candidate had been asked to bring a photo of the place that symbolized the region and was personally important to him (six of them) and her (one).(3)

The first of the candidates to speak was José Evrard, whose photo was of the mines around Amiens that had since closed. His father had been a miner and had fought in the Resistance; after the war, the miners had fought “the battle of coal,” without which the economic renaissance of postwar France could not have taken place. (He was standing next to Karima Delli, the environmentalist candidate.)

Evrard’s personal journey had taken him in many directions. He had joined the Communist Party as a young man; he had then moved to the National Front, and in 2017 had moved to Debout la France (DLF, or Rise up, France) one of the smaller but persistent parties on the right; he is a deputy in the National Assembly from Pas-de-Calais. His region, he said, during the mining days, had welcomed “selected” immigrants–”Italians, Poles, Moroccans”–who wanted to work, and who assimilated. In spite of his implied anti-(current) immigrant bias, he succeeded in telling a personal story about a place and his connection to it.

On the day of the debate, he was at 2% in the Ipsos poll.

Audric Alexandre, age 32, showed the Grand Place d’Arras and the great bell tower in the city hall.

Arras is his hometown, and is also the birthplace of Maximilien Robespierre, who spent his childhood and youth there until 1789, when he left for Paris as a newly elected member of the Third Estate. Alexandre did not mention the town’s connection with the revolution’s most infamous son. An attorney and professor of English and Spanish in the law school at Lille, he represents PACE, which means “peace” in a number of languages (though not in French) and he and his group stand for a united Europe–not perhaps the one we have, but a union of European nations that live peacefully together. They also believe, in an apparent contradiction, in a fully decentralized France, which devolves most tasks of governing to the regions.

He barely qualified for the race, managing to fill out his list of candidates by taking to social media and asking for volunteers. He was at 1% in the Ipsos poll. He will not go higher, but his reason for running is simply to promote the ideals of PACE. (3bis)

Next came Sébastien Chenu, the candidate of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, who showed a grievous lack of originality; he brought a map of the region. Lacking specific content to explain, he was able instead to give his standard stump speech–a lot of talent in the region, but high unemployment (obviously the fault of the incumbent); decades of alternating between the Socialists and Republicans, but no real change; time to try something different. He made a point of bringing up his origin in Picardy, since this part of the region had been vocally unhappy about the territorial restructuring that had put them in Hauts-de-France. He expressed his sympathy for the seven CRS police who had been injured in evacuating migrants (armed with stones, knives, hatchets, and golf clubs) from Calais the day before.(3ter)

Chenu was once a member of Les Républicains (previously UMP), and had left the party in 2014 when (driven by a very strong Catholic wing) the LRs opposed the same-sex marriage law (mariage pour tous) of 2013; he himself has long been openly gay. He is currently running second in the first round, with a score of 32%.

Laurent Pietraszewski is a member of Macron’s party, La République en Marche (LREM). Apparently inspired to enter politics by the En Marche! movement, he had first run for office in 2017, winning a seat in the National Assembly in the Nord department. He had a fast rise to Secretary of State for Macron’s now-stalled retirement reform; given the unpopularity of that attempt, his experience in that realm is not an asset. He brought a photo of adolescents on the street, in front of a school, their faces blurred for broadcast, to indicate his concern for the young people who have lived through the crise sanitaire. This choice was probably meant to indicate his future-facing program, though he did not entirely succeed in making that connection. His chief message in this campaign has been to tie himself to Macron’s government.

He was at 10% in the Ipsos poll, and thus still barely a contender; any candidate who receives at least 10% of the vote can choose to go on to the second round, or to make a deal (for posts, policy positions) with another candidate who has a better chance.

Karima Delli, born in France of Algerian immigrants, represents the Union de la gauche et des écologistes, a coalition of several separate parties on the left. During both of the debates (there was a subsequent debate on June 9) she found herself defending windmills as a part of an ecological transition. The body language is highly readable here.

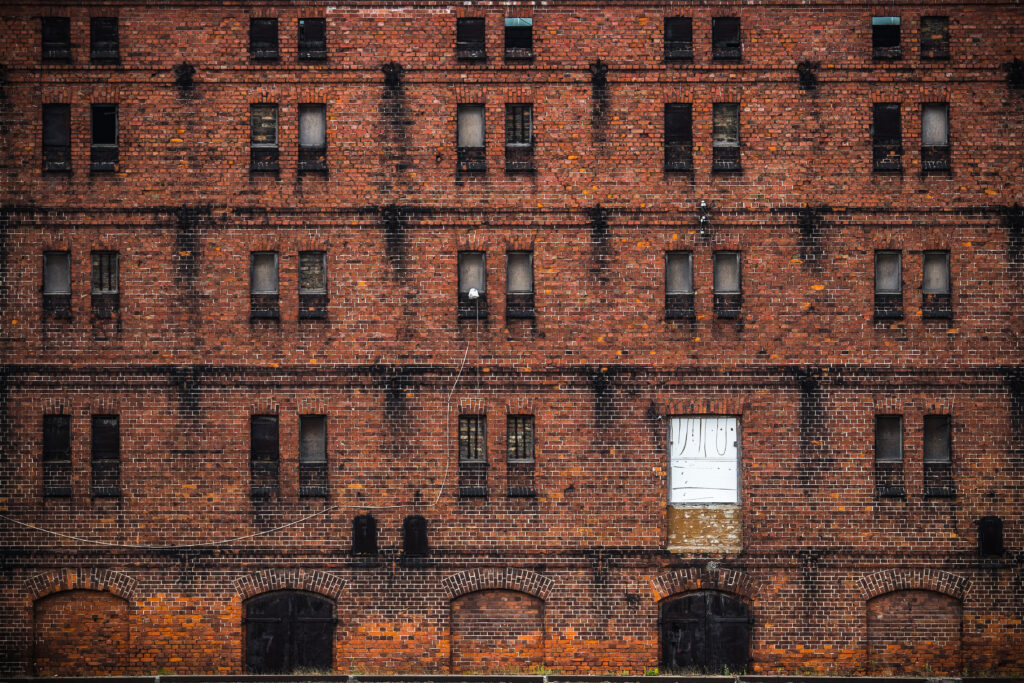

For the earlier June 2 debate, she brought a photo of the old brick textile factory, now closed, where her father had worked.

She is, then, a factory workers’ daughter, and in her home their family values were solidarité, fraternité, and dignité. She thinks, now, of the employees of Bridgestone (tires), of Cargill (agricultural processing), of Maxam Tan (ammonia nitrate)–three recent closings or restructurings that were costing the region hundreds of jobs. But, she added, they would not “allow the industry of yesterday to die, without creating the industry of tomorrow”–a good slogan signaling her commitments to both workers and the ecological transition. Certainly better than Macron’s Schumpeterian “economic life . . . is made up of creations and destructions.”(4) (And much better, as well, than Hillary Clinton’s tragic gaffe: “We’re going to put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business.”) (5)

Delli is third at 17% in the Ipsos poll of June 2.

Éric Pecqueur, the next candidate, is an official of the long-established Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT), the union that is no longer affiliated with the Communist Party but still very much to the left. He is running as the candidate for Lutte ouvrière (Workers’ Struggle, LO). The party is a Trotskyite spin-off of the Communists, and a small but persistent presence for decades on the national and local scene. Pecqueur is an auto worker at Toyota and a union activist. He brought to the debate a photo of PSA at Douvrin, an automobile engines plant threatened with closing, and a part of the multinational Stellantis group. “I was there yesterday,” he said, “handing out tracts with my comrades” (and there we are, back in the mid-twentieth century).

And here was Éric Pecqueur, walking the walk seven years earlier–speaking of the strike committee and votes taken, and with a fire (tires, probably), and honking horns in the background, at the Toyota plant:

The Stellantis group is owned, he continued at the debate, by “two wealthy bourgeois families, Agnelli and Peugeot” (they are the largest shareholders). They have decided to close their plants throughout Europe, in search of cheaper wage pastures; 1500 jobs are at risk if they close this plant. He is polling at 2% of the vote.

Xavier Bertrand came last, running under the banner of DVD (Divers Droite, or various parties on the right). He had left the LR party in 2017, when they had elected Laurent Wauquiez as president. (Wauquiez, accused by some of being too close, in policy areas, to Marine Le Pen, is also a very divisive figure; he resigned as leader in 2019 after the poor showing of the LRs in the European elections.)

Bertrand did not rejoin the LRs with Wauquiez’s departure, though they are supporting his list: he is effectively the only LR candidate in the race. He is also the incumbent president of the Région, and he is ahead in the polls with 36% of the vote (4 points ahead of Chenu), though–in some of the scenarios for the second round–he could lose, and then the National Rally would win the region. The photo he chose was from the end of May, 2020, a view of a large group of people marching to the Renault plant to demonstrate against a planned restructuring that threatened massive job losses. The people had come out in solidarity, he had led, Renault had stayed, and is even adding more jobs. A perfect example of his successful leadership.

Bertrand had told this story of saving Renault in March 2021, and had infuriated Macron’s government. The Minister of the Economy, Bruno Le Maire, had denounced him in La Voix du Nord, the major newspaper of the region. In an interview on France 3 Bertrand had gone a bit further, accusing the state of “having wanted to close the industrial site on the sly (‘en douce’)” but asserting that he, Bertrand, had “fought” side by side with unions and the region to stop the closing. Le Maire had then described this version of events as “a lie,” pointing out that the state is a major shareholder in Renault, and had worked hard with all the major stakeholders to persuade them to remain. In response, Christophe Coulon, vice president of the Région and an ally of Bertrand, said that Le Maire had told “a major lie”; Renault had in fact received the government’s permission to engage in this “strategic restructuring,” and only the region had saved them.(6)

The Régionales of Hauts-de-France, however, seem impossible to understand without reference to the Presidential elections of 2022. One would imagine that Macron wants a defeat of Marine Le Pen. The worst outcome, however, might well be instead the victory of Xavier Bertrand, who has already declared that he is running for president. The ever-talkative “proches” of Macron [those close to Macron] have indicated that he is genuinely concerned about the threat posed by Bertrand, a “social gaulliste,” in the race. Further, while Macron remains a few points ahead of Le Pen in polls on the first round, the polls also show that Bertrand would beat her more decisively in the second round than Macron would (60-40% for Bertrand and Le Pen, 54-46% for Macron and Le Pen).

Thus Macron has “nationalized” this race by sending five members of his cabinet (and subcabinet) here, two of them in major posts. Gérald Darmanin, the Minister of the Interior (and a former LR, formerly close to Bertrand) is in the next-to-last place on Pietraszewki’s list for the Nord department: thus he will not be in danger of taking a seat on the regional council. But as a tested campaigner in the region (Darmanin in fact directed Bertrand’s first regional campaign, against Marine Le Pen herself, in 2015), he knows the territory. Moreover, as Minister of the Interior, Darmanin can play the migrant card, as he did on Sunday, June 13, by ordering prefects to expel foreign undocumented troublemakers from their departments (covered thus far by Le Monde, Le Point, Orange actu).

Macron also sent Eric Dupond-Moretti, Minister of Justice, to run as the head of the departmental list for the Nord.** Dupond-Moretti, one of France’s most prominent defense attorneys, made a grand entrance: “In contrast to M. Bertrand, I don’t want to hunt on the lands of the RN. I want to chase the RN from this land.” (Chasser means both hunt and chase.) There is a great deal of speculation to the effect that Dupond-Moretti and Darmanin were both sent to bolster Pietraszewski’s campaign, to make sure he gets above 10% of the vote, so he can make a deal or be a spoiler. Bertrand has said, preemptively, that he will not make a deal with LREM for the second round; he referred to Macron as “a crude calculator, a destroyer.”

Darmanin has said that an RN victory in Hauts-de-France would be “a mark of Satan.” (7)

Dupond-Moretti, in passing by a sidewalk café, ran into Damien Rieu, a candidate for the RN, who accused him of being Macron’s pitbull and wearing a Rolex. Dupond-Moretti denied that it was a Rolex. Rieu told him to do his job as Minister of Justice; Dupond-Moretti said not to tell him what to do.

Karima Delli said, “All of that, it’s political spectacle. We, our objective, is to change peoples’ lives.” (8)

========================================================

*The President of the Regional Council is elected by the members of the regional council by an absolute majority of the members; if the absolute majority is not attained after two votes, then the third round can settle the issue with a relative majority. https://www.vie-publique.fr/fiches/19627-quest-ce-quun-conseil-regional. The election is partly proportional, with 75% of the seats apportioned according to the percentage of the vote received by each list. The remaining 25% of the seats go to the winning electoral group. The likelihood of actually sitting in the Regional Council depends on how far down one is on the list. This system is used for allocating Municipal Council seats, and for allocating seats in the European Parliament.

**Voters vote for the names on the regional list by department; thus each department has its own list, which is a part of the regional list.

================

(1) “Elections municipales à Hénin-Beaumont: Le frontiste Steeve Briois réélu dès le premier tour,” 20minutes.fr, March 15, 2020 https://www.20minutes.fr/municipales/2740587-20200315-elections-municipales-henin-beaumont-frontiste-steeve-briois-reelu-premier-tour (accessed June 12, 2021); Romain Berchet, “Municipales: Steeve Briois largement réélu à Henin-Beaumont,” France bleu, March 15, 2020. https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/politique/municipales-steve-briois-largement-reelu-a-henin-beaumont-1584306560 (accessed June 12, 2021).

(2) “FN: ‘Pas de vote protestataire, plutôt un vote d’adhésion,'” Le Monde, March 24, 2014. (accessed June 12, 2021). https://www.lemonde.fr/municipales/video/2014/03/24/fn-pas-de-vote-protestataire-plutot-un-vote-d-adhesion_4388472_1828682.html (accessed June 12, 2021).

(2bis) “Régionales: Sébastien Chenu (RN) estime que l’éolien est une ‘escroquerie,'” BFM Lille, video, June 3, 2021.https://www.bfmtv.com/grand-lille/replay-emissions/lille-politiques/regionales-sebastien-chenu-rn-estime-que-l-eolien-est-une-escroquerie_VN-202106030449.html (accessed June 13, 2021).

(3) See the video here: https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/hauts-de-france/regionales-2021-hauts-de-france-suivez-en-direct-le-debat-entre-les-sept-tetes-de-liste-sur-france-3-2117596.html (embedded within the article)

(3bis) Jean-Louis Manand, “Régionales 2021 Hauts-de-France: Audric Alexandre, l’Européen,” France3 Hauts-de-France. https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/hauts-de-france/regionales-2021-hauts-de-france-audric-alexandre-l-europeen-2096752.html

(3ter) Adrien Boussemart, “Calais: rixe au couteau entre une trentaine de migrants, quatre blessés, La Voix du Nord, June 2, 2021. https://www.lavoixdunord.fr/1017533/article/2021-06-02/calais-rixe-au-couteau-entre-une-trentaine-de-migrants-au-moins-quatre-blesses (accessed June 12, 2021; Louise Thomann, “Sept CRS blessés après de violents affrontements avec des migrants à Calais,” Francebleu, June 2, 2021. https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/faits-divers-justice/sept-crs-blesses-apres-de-violents-affrontements-avec-des-migrants-a-calais-1622663441 (accessed June 12, 2021).

(4) “Macron, Ruffin, Whirlpool . . . and an Old Audiotape,” Reflectionsonfrance.com (this blog).

(5) David Roberts, “Hillary Clinton’s ‘coal gaffe’ is a microcosm of her twisted treatment by the media,” Vox, September 20, 2017. https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/9/15/16306158/hillary-clinton-hall-of-mirrors (accessed June 12, 2021).

(6) Mathilde Durand, “Industries dans les Hauts-de-France: Bruno Le Maire répond à Xavier Bertrand et dénonce ‘des mensonges,'” Le Journal du Dimanche, March 19, 2021. https://www.lejdd.fr/Politique/industries-dans-les-hauts-de-france-bruno-le-maire-repond-a-xavier-bertrand-et-denonce-des-mensonges-4032561 (accessed June 12, 2021).

(7) Alexandre Lemarié and Sarah Belouezzane, “Présidentielle 2022: Emmanuel Macron se méfie de Xavier Bertrand,” Le Monde, June 2, 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2021/06/02/presidentielle-2022-emmanuel-macron-se-mefie-de-xavier-bertrand_6082446_823448.html (accessed June 12, 2021); Olivier Beaumont, with Marcelo Wesfreid, “Régionales: Xavier Bertrand et Gérald Darmanin, des amis devenus adversaires,” Le Parisien, June 13, 2021. https://www.leparisien.fr/elections/regionales/regionales-xavier-bertrand-et-gerald-darmanin-des-amis-devenus-adversaires-13-06-2021-ZOCW724PLVAFVNCBURTKJUNFYM.php (accessed June 12, 2021)

(8) Dinah Cohen, “Régionales: les Hauts-de-France, épicentre d’une campagne nationalisée,” Le Figaro, May 11, 2021. https://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/regionales-les-hauts-de-france-epicentre-d-une-campagne-nationalisee-20210511 (accessed June 12, 2021).