Campaign Chronicles: Fabien Roussel

Since Emmanuel Macron has refused a regular debate before the first round, TF1 came up with a substitute format–a succession of candidates, each alone on the stage, each giving a closing statement, and answering the questions put forward by two moderators. The candidates took varying amounts of time, but were roughly between 18-20 minutes–about the amount of time they might get, or a bit more, in a regular multi-candidate debate. Without interruptions. Without pre-scripted “zingers.” Without shouting over each other. Without the shouting of the questioners, as they tried to keep order. It worked, and it’s something that the United States, in these early multi-candidate debates, might consider.

The order of the candidates was determined by the drawing of lots. Someone had to be last, and that was Fabien Roussel, the Communist Party candidate (PCF). His turn came at the end of nearly three hours, and he gave an audible sigh as he stepped on stage, wearing a blue and yellow boutonnière on his lapel.

The first question was about Ukraine and he said, directly and without the hedging or reluctance that characterized certain other responses, that Putin was the aggressor and that he had violated national sovereignty and international law. He included criticism of the United States as the “grand gendarme of the world,” but “let there be no mistake”–there was one aggressor in this situation, and that was Putin.

Like other candidates who have proposed leaving NATO, he said that “of course” France should not leave NATO now, in the midst of war, but down the road, there should be another kind of security force of the European continent (presumably excluding the United States).

And as for what he would do in the current situation? What Macron has done; he stated that France should “speak with one voice” in foreign conflicts.

Sounds like a great idea.

The last time that the Communist Party of France (PCF) ran an independent presidential candidate was in 2007, when Marie-Georges Buffet came in with under 2% of the electorate. In 2012 and 2017 the Party supported Jean-Luc Mélenchon as the candidate of the Front de Gauche (2012) and then of La France Insoumise (2017). Such a strategy–the union of the Far Left–has risks for the Communist Party, and one of them is the slow sinking into irrelevance, and the loss of seats, both in the National Assembly and throughout France.

When Fabien Roussel was elected as head of the Party, in 2018, he did so with an explicit pledge to run a separate presidential campaign. He is at about 4-5% in polls–which might be, some fear, just enough of a percentage to keep Mélenchon out of the second round. This conventional wisdom may be wrong; it’s not clear that French voters are torn between varieties of the left, but rather between varieties of populism, whether left or right.

Perhaps Roussel’s biggest obstacle is to explain how he differs from Jean-Luc Mélenchon and La France Insoumise (LFI). Many commentators have suggested that he has successfully done so.

Roussel did so in this debate, for example, by reiterating his support of nuclear power: it is cleaner, it puts price controls within the control of the nations, and France’s nuclear power grid is an “enormous asset.” Windmills and solar power alone, he suggested, won’t do it.

He has separated himself simply by running separately, despite the great pressure to unify the Left.

Perhaps most importantly, he has broken with LFI in regard to Islam and its place in France. Roussel has not gone down the route of attacking immigration, which is well-covered by the right; rather, he has focused on culture, and on a very strict version of laïcité, or secularism. Secularism might be defined as keeping religion out of government; a more rigorous form, which Roussel follows, refers to keeping religion out of the public sphere entirely–no overt signs, no religious dress, no public prayers. The 2004 legislation (under Chirac) that banned headscarves and other overt religious symbols in public schools reflected that ideology; so too did the 2010 ban (under Sarkozy) of burqas, and headgear that covered the face, in public.

On January 9, 2022, he tweeted what seems like a fairly innocuous statement, calling for a more just division of wealth: “Good wine, good meat, good cheese: that’s good French cooking.” The best way to defend it, is to permit the French to have access to it.”

All heck broke loose.

Roussel was accused of cultural insensitivity. Not everyone drinks wine. Lots of people like couscous. What about the climate, and the environmental cost of animals? Meat might mean pork, and not everyone eats pork. (Valérie Pécresse included a small nod to the controversy in her Zenith speech, changing the wording to “Charolais [cattle] and wine.”)

He had committed other acts that had offended, including taking a prominent role at a commemoration of the Charlie Hebdo massacre–alongside Caroline Fourest, a prominent feminist and critic of what she calls “Islamic Totalitarianism.” One of the members of his party, Deputy Elsa Faucillon, tweeted her displeasure.

“Obviously the PCF can and should organize homages to Charlie. Last evening went well beyond homage: the selection of guests confirms a political turn carried out by my party for the past several months. And the Printemps républicain [a secularist group that is opposed to “political Islam”] is rubbing its hands together [in glee].”

Amar Bellal, member of the PCF national bureau (and Roussel’s advisor on energy) described the tweet as “indecent,” noting that the families had wanted this tribute, that Fourest and others had been friends of Charb [Stéphane Charbonnier, the director of publication of Charlie Hebdo and killed in the shooting), and that as such they had a right to be there.

With these acts Roussel has commanded attention as a victim of wokisme–to the point that some have suggested he might have provoked all of this deliberately.

The PCF believes in the classic class struggle of workers against capitalists; LFI believes in intersectionality–that society itself, including the laboring classes, is divided by gender, race, and religion, as well as by class. Under Roussel, the PCF stands for militant secularism; LFI has been notably receptive to a softer version, which allows for the existence of and supports the tolerance of all religions, including their visibility in the public sphere.

Whether Roussel’s acts, including the tweet, were intentional or not, he has succeeded in differentiating the French Communist Party from La France Insoumise rather decisively.

==========================

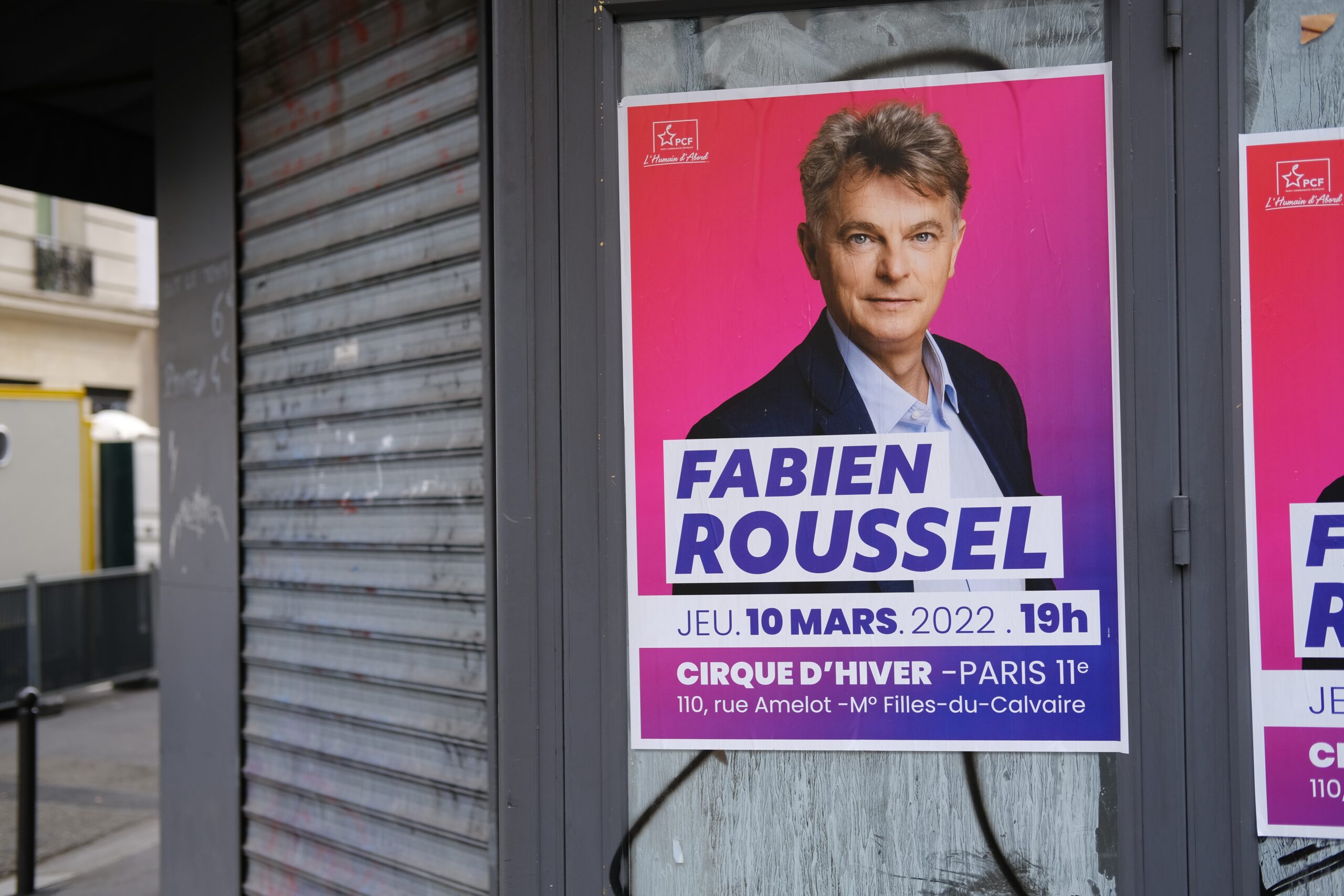

Header Image from Shutterstock.com.

==========================

The full debate of La France face à la guerre can be seen on tf1.fr. Snippets of it can be seen on YouTube.

Amine El Khatmi, “‘Soutenir Fabien Roussel face aux attaques, c’est soutenir une certaine idée de la gauche,’” Marianne, January 14, 2022.https://www.marianne.net/agora/tribunes-libres/amine-el-khatmi-soutenir-fabien-roussel-face-aux-attaques-cest-soutenir-une-certaine-idee-de-la-gauche

Céline Pina, “Fabien Roussel, candidate de la gauche laîque et républicaine sacrifié sur l’autel du wokisme,” Le Figaro, February 9, 2022.https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/politique/fabien-roussel-candidat-de-la-gauche-laique-et-republicaine-sacrifie-sur-l-autel-du-wokisme-20220209

Hadrien Brachet, “De laïcité au nucléaire: Elsa Faucillon, la députée communiste anti Fabien Roussel,” Marianne, February 4, 2022.https://www.marianne.net/politique/gauche/de-la-laicite-au-nucleaire-elsa-faucillon-la-deputee-communiste-anti-fabien-roussel