Macron, Ruffin, Whirlpool . . . and an old audiotape

A longtime nemesis suddenly revealed as a secret collaborator. François Ruffin, a self-proclaimed man of the people, unmasked as the clandestine partner of Emmanuel Macron, “president of the rich,” helping him to stage their disagreements for public consumption.

Betrayal.

Hypocrisy.

Well: not exactly. But it shook the twitterverse for several hours last week, just after Macron’s third return to the abandoned Whirlpool plant in Amiens.

So here is the backstory.

The Whirlpool factory site in Amiens dates back to 1910, when it manufactured agricultural equipment. Washing machines were first produced there in 1958 by Philips, which was bought up by Whirlpool in 1990. It had then employed 1,000 people; modernization, robotization, had reduced the workforce to 290. In 2014 Whirlpool had acquired Indesit, an Italian company that brought with it many factories throughout Europe. There were soon rumors that the plant was going to close (Le Figaro, April 26, 2017.)

And in fact it did, at the beginning of June 2018, when production was finally moved to Lodz, Poland, over a year after the departure was announced. The 57,000 square meter site had been taken by Nicolas Decayeux, a local businessman who planned to reconfigure half the structure to manufacture chargers for electric vehicles and refrigerated lockers. The other part of the site would be rented to small businesses (PMEs) and used for TPEs, which means “supervised personal work,” and refers to students who are attempting to finish a project for graduation–thus a sort of incubator (Le Figaro, May 31, 2018).

No, it didn’t sound very hopeful, even to those who desperately wanted to believe that it would work. Nevertheless the deal with Decayeux had been finally reached in September 2017, with the promise of 277 new jobs (Reuters, September 12, 2017). (And a personal note, if I may: early in 2006, Whirlpool bought the Maytag Company and, a few months later, closed the historic 1893 original plant and headquarters in Newton, Iowa. My father, who had grown up on an Iowa farm, was a regional sales manager with Maytag and, though long retired, was heartsick at the news of the closing of the Newton plant. The sorrowful last days of any venerable factory–the progressive shutting down of production, the emptying out of the warehouses, the removal of machines–are the same everywhere.)

This new electric-charger venture had indeed collapsed, and Macron returned in late November, 2019, to speak to the former workers, accompanied by Agnès Pannier-Runacher (green blouse woman), undersecretary of Labor. She blamed the failure on Nicolas Decayeux, the entrepreneur and would-be savior. The plan had seemed a good one, but the problem was commercial–the entrepreneur “had not known how to find customers.” All that was left on the site was Ageco Agencement, which hired only 44 of the old Whirlpool employees, for a total of 100 workers making office furniture (Le Journal du Dimanche, November 27, 2019). Macron had made a partial circuit of the old Whirlpool factory, now clearly underused.

Macron also met there the deputy of the Somme (including Amiens) François Ruffin, of the far left La France Insoumise. You would be a bigger man, said Ruffin, if you admitted that this situation “was f•cked up” (Le Figaro, November 22, 2019). In fact Ruffin wanted to convey two things: that; and his demand for a direct contact, an “interlocutor,” at the Elysée, so that he could ensure that Macron was kept informed of what was actually going on in Amiens, directly, and without endless bureaucratic delays.

This made the news. But it was by no means the first encounter of Ruffin and Macron. Far from it.

François Ruffin, a journalist, author, and filmmaker as well as a politician, is the author of a book-length takedown of Macron, Ce Pays que Tu Ne Connais Pas (This Country that You Don’t Know, 2019). The two have a long acquaintance: both were born in Amiens, both attended the same lycée, la Providence, and by Ruffin’s account, the two-years-younger Macron was the golden boy of the school, beloved by all his teachers (one especially) while he, Ruffin, was the rebel hiding behind his notebook and hoping he wouldn’t get called on. When Macron entered public life, first as Minister of Economy, Industry, and Digital Economy (du Numérique) under Socialist Party President François Hollande, and then in his quest for the Presidency, Ruffin had sought to confront him.

He had resented Macron because, as Minister, he had pushed Socialist President François Hollande “to the right, always farther to the right. As if all the social forces, the Medef [employer federation], the press, the European Commission, etc., didn’t already push him there. As if, especially, [Hollande’s] own inclinations did not suffice” (Ruffin, p. 49). “I hate you less now,” he writes in 2019, as if speaking to Macron. “The imposture is finished: you are officially on the right, the ‘president of the rich’” (Ruffin, p. 41).

On April 6, 2017 (the first round of the presidential election was a little over two weeks away, on April 23), Macron appeared on the show L’Émission politique, which has an extra feature called l’inattendu–the “unexpected,” a mystery guest who would be questioning him along with the hosts. Macron drew Ruffin as his surprise, introduced here as an activist in the recent Nuit Debout movement against labor law changes.

Ruffin was not at his most eloquent, and Macron was. Nevertheless, the two had some revelatory exchanges. Ruffin spoke of those left adrift by factory closings, especially of those businesses that migrated to low-wage countries; Macron, he said, always spoke grosso modo–vaguely–but let the plants close, all the same. Macron stated that “economic life . . . is made up of creations and destructions.” Those in temporary jobs would do well to get training, rather than remain in “sectors that had no future”; he concluded with an anecdote of a young man who had retrained, and was now the manager of his workshop (begins at 7m30s). The perfect technocrat with the standard solutions.

Ruffin stated (beginning 9m20s) that Macron’s published economic reform plan (which would soon unfold as entirely a matter of regulating labor and relieving high-end taxes) included nothing about regulating shareholder dividends and CEO salaries, which had seen explosive rises since the 1980s, nothing about the regulation of banks, nothing about paradis fiscaux (tax havens). Macron became visibly impatient, and finally (11m49s) broke in: “First of all, you’re a man of conviction; we don’t have the same convictions, but I see you as a free man and your battles are your battles; yes, . . . [interruption] . . . I don’t have the same battles that you have, but I have my battles. I’m as free as you are, as free as you are, and I don’t need lessons on liberty. In my life I’ve known how to say no, I’ve said it on several occasions. I’m no one’s hostage and I don’t serve anyone, and I have this dignity, as you do. . . . I don’t like the insinuations.”

Macron was answering the subtext rather than the text: Ruffin had no doubt made his “insinuations” before, and later made them explicit in his book about Macron, beginning with La Fontaine’s fable of the dog and the wolf. The dog was pampered while the wolf had a hard life. But the dog had a collar and leash; the wolf decided upon liberty, even with all its hardships. “I see it, the collar,” Ruffin wrote, “tight around your neck, strangling you, stifling you. They [the bankers and CEOs] have so well fed you, so well filled your duffel, that you are today their creature” (Ruffin, pp. 122-123).

But out of this television show Ruffin obtained a grudging promise that Macron would go to the Whirlpool plant in Amiens. This gave rise to the most iconic moment of the second round presidential campaign, which was a contest between Macron and Marine Le Pen, as shown in this English-language broadcast:

As Ruffin described the optics of this visit, there was a stark contrast: “You, seated, in a suit, technocratic, rigid,” while “the malignant Marine” came directly to the workers, embraced them, took selfies. Ruffin himself came to the plant after “the Le Pen show” and was peacefully eating barbecue with the workers when the news spread that Macron was coming. The following film, in typical immersive Ruptly fashion (owned by RT, both funded by the Russian government) showed scenes from the chaotic parking lot, including Alexandre Benalla (dark grey puffcoat man), the notorious bodyguard, at Macron’s side (more about him in another post). Macron left, and the workers threw another tire on the bonfire (a frequent feature of labor protests).

The woman in the video is largely drowned out, at least to me; the man states that he is neither for Le Pen, nor Macron, but for keeping his job. Ruffin had given Macron a megaphone, but Macron was unable to make it work. And so Ruffin, for reasons he did not understand himself, had organized a way out, that allowed Macron to go directly to the workers for a brief dialogue while the journalists stayed behind the barrier (Ruffin, pp. 132-134).

Ruffin later admitted that he would have enjoyed the spectacle of “the banker chased by the proletariat,” but in the end, “I participated in keeping order! Why did I do that?” He still didn’t know. Class loyalty of the bourgeoisie? Deep-seated fear of the crowd? “Or the desire to save a man, to hold out my hand to him, even an adversary, even you?” (Ruffin, p. 136).

Not only was Macron pulled from an embarrassment, from being driven out by the boos of his hometown crowd, claimed Ruffin, but he was even praised for his courage in confronting the workers head on, a reputation that has continued. “The president does not run away from difficulties,” stated Pannier-Runacher during the latest trip (Financial Times, November 22, 2019).

Macron’s second visit to Whirlpool occurred in October, 2017. Macron, pictured in a yellow vest, toured the factory with the new entrepreneur, the soon-to-be-under-the-bus Decayeux. Macron had, of course, every reason to want this new start-up to work: the nation’s eyes were on the Amiens site, and the credibility of Macron’s economic vision rested, to a certain extent, on seeing this new venture succeed, on showing that “destruction,” as he had said, is followed by “creation.” However, as the English-language news report below also reveals, the closing of Whirlpool in the following year would plunge underwater the various subcontractors who had supplied the plant; what would become of them?

What followed, then, was the closing of the new venture and yet another trip to Amiens just days ago in November, 2019. Ruffin, who arrived on his bicycle, explained to reporters the anger of those who were waiting for him: “To come here two years ago to tell the employees that they will be hired again, is to take us for fools. To return two years later to say he is disappointed, is to take us for fools twice” (Le Figaro, November 22, 2019). (Or, as George W. Bush said, in the retooling of an old saying, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, won’t get fooled again.”). And then, as noted above, he asked Macron to admit, as the Financial Times decorously expressed it, that he “had screwed up.”

Just a few days later, the mini-bombshell.

Juan Branco, a leftist attorney and journalist, a supporter of the Gilets Jaunes, posted an audiotape that showed that Ruffin and Macron had played a cruel game, especially on those who relied on Ruffin. This tape went back to an earlier factory closing in 2016 involving Ecopla, a small firm (77 employees) that built aluminum molds, sheds, and other aluminum products. The employees had been trying to contact Macron, then Minister of the Economy, but their letters had gone unanswered. Macron had left the Ministry, in preparation for his likely presidential run, and Ruffin led a small group to Macron’s headquarters in Paris:

Here is the translation of the video, including the audiotape of Macron and Ruffin; then an excerpt from the most recent confrontation at Amiens; and then an ad for Branco’s book, Crépuscule:

Tour montparnasse, September 12, 2016. 14th floor.

The employees of Ecopla came to the headquarters of Emmanuel Macron to plead their case.

They had just been the target of an extremely violent pillage by stockholders.

François Ruffin, who accompanied them, had suggested that they negotiate with Emmanuel Macron.

The employees, caught in a vise, allowed [Ruffin] to guide them.

They were about to be manipulated by these two politicians.

(Then the audiotape)

Ruffin: Yeah, I think that if we consider strategy, the best is for you to be sharply and publicly questioned by the employees of Ecopla . . . that would be an episode . . . and then you, you could respond by saying: well, I’m ready to go there, and that is the second episode.

Macron: Ok. Ok. So first, we discuss this case; second, we bring you up to date; third, you, you question me publicly; fourth, immediately afterwards figure out a date, before 5 October; and, and we’ll see how we communicate . . . together

Ruffin: And I think we get out of here, not happy . . .

Macron: Yes, saying that you told me about . . . and here it is.

Ruffin: Here it is. If not all this . . . here it is.

Then back to titles:

September 12, in the evening, 161 rue Montmartre.

Everything came out as planned by MM. Ruffin and Macron.

Outside, in front of the media, François Ruffin acted out his opposition to Emmanuel Macron.

Macron impressed the media with his calmness,

[Crowd shouting, “Macron, Président!]

And obtained the following week, a “peaceful” visit with Ecopla, on September 20, 2016, which was the launch of his campaign on the theme of industry,

[A series of still photos.]

before abandoning them.

Five months later, the employees of Ecopla threw in the sponge.

They understood that they had been used.

When the judicial decision in their favor came down, on May 5, 2018, they had long since been forgotten.

François Ruffin, who had surfed the media thanks to their combat, was elected deputy.

He would repeat the scene at Amiens with Emmanuel Macron on two occasions with the former employees of Whirlpool, identically manipulated,

Demanding that one not call into question his “sincerity” before an Emmanuel Macron happy to participate in new productions.

The media are enchanted.

[Then at Whirlpool, with Ruffin visible behind the blond woman at the left of the screen.]

Woman speaking: Monsieur, I would like to emphasize that M. Ruffin has been with us since the beginning, he’s the only one that we know who takes risks for us, and we need a lot more deputies like him, if you could do something so that all deputies can do their jobs better [Ruffin and Macron both smiling].

Macron: (a bit unclear, but “they’re your deputies.”)

Woman: You don’t demand much of them and there’s no praise for M. Ruffin, one can be for him or against him, but frankly, he’s truly a good man, I say bravo.

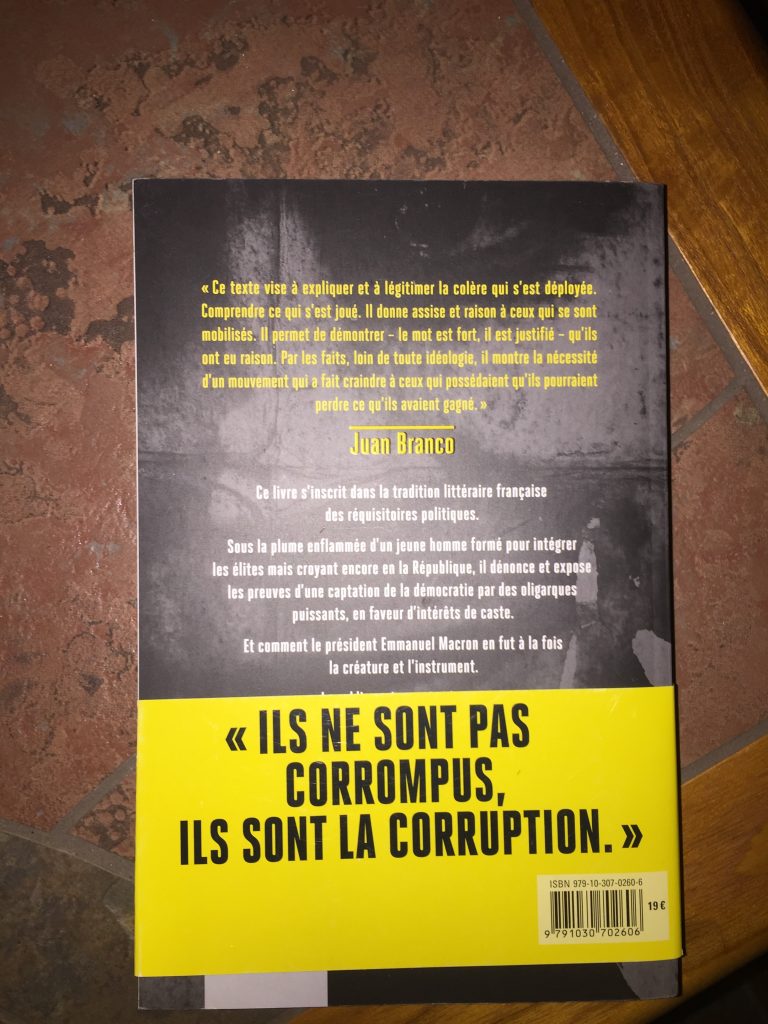

[Back to black screen]: They are not corrupted. They are the corruption (the band around Juan Branco’s book, Crépuscule.)

This revelation did not hurt Macron; duplicity is expected of him, whether fairly or not. Nevertheless there was a firm denial from the Elysée that any such staging had occurred at Amiens ( in Le Figaro, November 26, 2019 which also published the initial charge and Branco’s video). But the most essential part of Ruffin’s identity is his blunt honesty and his uncompromising stance in favor of workers. The suggestion that he had collaborated with Macron in a contrived public demonstration meant that this exposé was aimed at him, not Macron.

There were a few problems, however, beginning with the fact that this audiotape was not newly “discovered,” but had been played on Radio Nova, October 1, 2016, in full (a little over six minutes). Nor was it secretly recorded without Ruffin’s knowledge, since he discussed his tactics openly in the broadcast. The Radio Nova package unrolls as follows:

The announcer begins by stating that the story of Ecopla is one that has become “ tragically banal,” a plant closing and the unemployment of all the workers. Ruffin explains to her that he had wanted to help this small company (only 77 workers) “to exist in the public space.” The key to that was Macron, surrounded by light, and they had hoped to “take a little of this light so they could [be seen to] exist.” He had thus gone with a small group of the workers to confront Macron at his headquarters in Paris.

Then we hear Macron, angry, who argues that the proper procedure is the redressement judiciaire, the judicial investigation of the status of the enterprise (which had already started, on March 9, 2016, and finally ended in judicial liquidation; see Procedurecollectif.fr). They spoke, says the announcer, for an hour. The announcer also mentions the workers’ right to buy an industry that is closing by establishing a cooperative, and they are supposed to have the first chance–”like the tenant of a building going up for sale.” That had not worked out either (see L’expresse entreprise, n.d.; L’expresse entreprise, July 10, 2015).

Then we go to the “bombshell” audiotape, extracted for Branco’s youtube video. Significantly, however, we hear on Radio Nova something we didn’t hear in the youtube video; when Macron says he will agree to go to the plant, a woman’s voice says, “before October 5,” which Macron repeats. The two men were not, then, alone, as implied, but had at least one person present; the nature of the interjection suggests one of the workers rather than the radio personnel, but whatever the case, it is the voice of an observer, deliberately omitted from the bombshell release. [It should be noted that at least one other person noticed this voice, and has now commented on the soundcloud audio.]

Macron semi-apologizes to the workers (who are shouting Vive Ecopla) and promises to come to the plant.

At the end of this 2016 broadcast, the announcers themselves express some surprise at this stagecraft between the two opponents. Ruffin answers by suggesting that there is no “permanent enemy,” that Macron was the enemy of “yesterday,” but in future perhaps he could do something for Ecopla.

Ruffin had done, in a sense, what he would later do in the first Amiens encounter: he had tried to calm the situation, to provide a face-saving exit ramp, and (in both cases) had shed some light and extracted a promise of further attention without compromising the relationship.

Had he compromised too much?

Branco and Ruffin exchanged bitter tweets:

From Ruffin: Let those who give lessons lead these social battles other than on Facebook posts.

From Branco: Let ‘political’ leaders stop lying and setting up false confrontations.

Libération spoke to Sylvain Laporte, Ruffin’s parliamentary assistant, who confirmed that about a dozen of the Ecopla workers had been with Ruffin during this conversation with Macron; the conversation had not occurred behind their backs. Ruffin had responded to Figaro: “I was in a fight to save the employees of a place in the depths of Isère. I had a Macron card to play, and I played it. And I also played some other cards with other presidential candidates at the same moment” (Libération, November 26, 2019).

So what was this all about, really? Juan Branco, at 40 years old, is a well known attorney. He claims that he acted on principle, arguing that such negotiated confrontations were of the sort that would shake public confidence in their representatives, adding, “Nothing justifies acting in this way, regardless of the ideas or interests that one is defending at the moment” (Les inrocks, November 27, 2019). (It’s a good point, though it doesn’t excuse his own presentation of the tape.) His most prominent clients have been Julian Assange, of Wikileaks, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, head of the party to which Ruffin belongs.

Interesting.

========================================

Header image is from Shutterstock.com.

Ruffin, François. Ce Pays que tu ne connais pas. Paris: Les Arènes, 2019.