Unnatural Disasters: Migration, Senegal, Europe

Review of La Pirogue (Senegal/France, 2012), directed by Moussa Touré.

Review of Anna Badkhen, Fisherman’s Blues: A West African Community at Sea (New York: Riverhead Books, 2018).

France was in Senegal beginning in 1677, when they seized the island of Gorée in Dakar’s harbor as a trading post. They retained control of the coastal area after the Napoleonic wars, and in the late nineteenth century they extended their control inland, as part of their west and central African empire. Gorée is now a World Heritage site, as a memorial to the slave trade; the bigger slave station was Saint-Louis, to the north. But slavery and the slave trade, a foundation of capitalist wealth, scarred the landscape here as elsewhere; imperialism and the exploitation of local resources continued post-slavery. The Senegalese Tirailleurs were an important fighting force for France in both World Wars.

The colonial period ended with Senegal’s independence in 1961 but, as with every country subjected to European rule, the empire did not really end but merely transformed into something else formed of economic bonds and corporate development. Just as Europeans headed south (and east and west), Africans now head north.

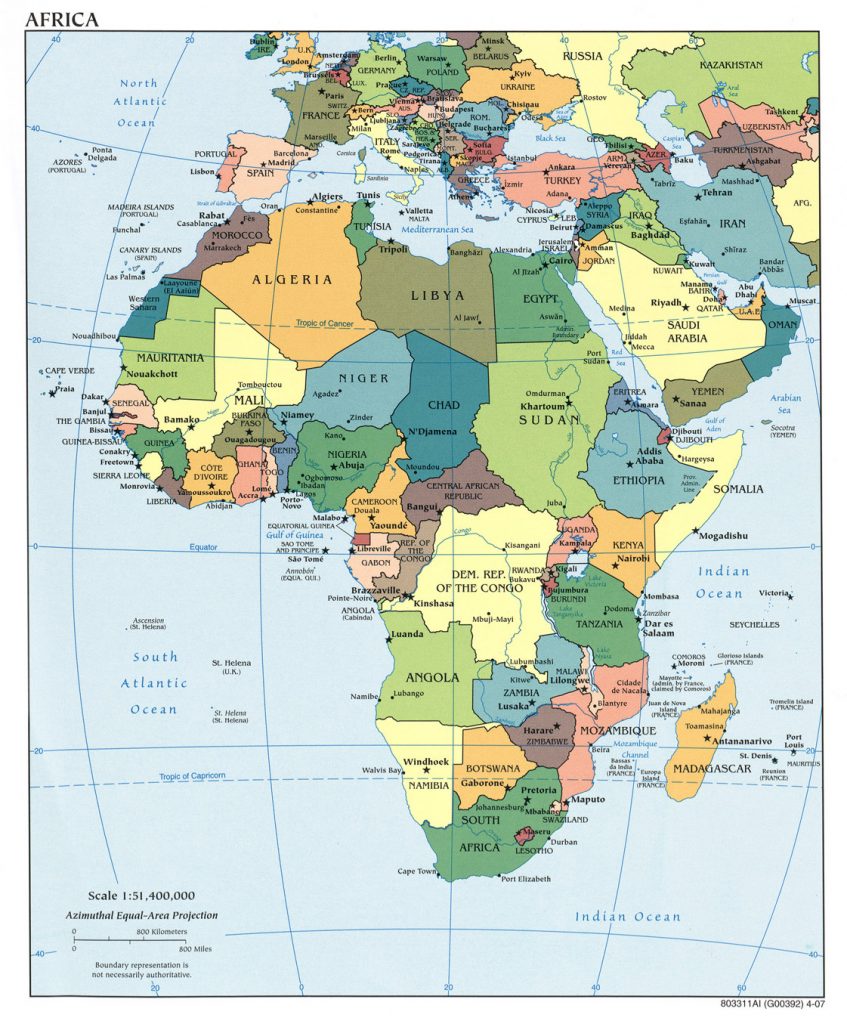

The Pirogue, a 2012 Senegal/French production directed by Moussa Touré, was filmed well before the 2015 migrant crisis, when the world became familiar with the images of overcrowded small boats adrift on the waters. But those boats were on the Mediterranean; Senegalese migrants often went, and continue to go, by way of the Atlantic, with the Canaries as their first destination. They look for fishing boats with captains who are willing to try for Europe, despite the dangers of braving the stormy Atlantic in small boats that will be forced to go well beyond the coastal waters they are built for.

This film shows us the assembling of a boatload of men who want to leave. Lansana is the organizer and self-proclaimed “cop” of the boat, though Samba, the distinguished natural leader of a Muslim group from Guinea, exercises his influence more effectively. Nafy is the only woman and a stowaway, because otherwise they would not have taken her; there are some perfunctory mutterings about “bad luck,” but nothing serious. YaYa is the man with the chicken; when the chicken is killed on the high seas, as it finally must be, it is done reverently and with kindness. Kaba is young, has some experience with the boat but not enough; he is swept overboard in a storm, taking the GPS with him. Baye Laye, a fisherman who knows the Atlantic, is the captain and the owner of the boat, who does not wish to leave but feels that he must; his catches are declining and his livelihood is going away. Abou is his younger brother, who believes he will be scouted by a soccer (football) team in France. He isn’t worried about becoming an illegal immigrant; the team who hires him will take care of his papers. And then he will take care of his brother, who knows only fishing. The boat itself is sturdy and bravely painted; it has a backup engine, in case the first is defeated by the rough waters of the Atlantic.

The people who make the choice to migrate are not in immediate danger. They are not in flight from political tyranny or civil war, as were the Syrians who swelled the ranks of the migrants to a crescendo in 2015. Rather they are, like many migrants, facing an accelerating deterioration of their livelihoods. Baye Laye, the captain and owner of the small boat that gives the film its name, is a fisherman who is finding it increasingly difficult to catch enough fish to support his family. His wife does not wish him to go, but he has no economic options except the ocean, and it is no longer as generous as it used to be.

Others have different reasons. Abou has his soccer dream. Another man lost a leg when his fishing boat got too close to another, and he is going in hopes of a decent prosthetic. Nafy has “a job waiting for [her] in Paris”; she lost her husband when he made a similar desperate attempt. Samba has the address of someone who can get him agricultural work in Andalusia, but is under no illusions that it will be a better life, and he is already homesick for the beauty of the land he left behind. There are those who go because of the one person they know or have heard of who struck it rich and came back to build the biggest house in town. Still others have anxious hopes riding on them. “My entire village is depending on me,” says one of the passengers in anguish; remittances from Europe are what keep many families going (Reuters, April 24, 2015.). All of those on the pirogue are aware of the risks, and know that one boat in ten doesn’t make it; but staying in Senegal means “ten chances out of ten that you fail your life.” As one of the characters declares, “I’m an African man who decided to enter history by his own means!”

When the film is on land, it is Beyond Thunderdome: a heat-blasted landscape, naturally arid land now too often turning to drought, and the detritus of multinationals–an iPhone, a Gap t-shirt, a football jersey for Real Madrid. As Senegal expatriate Salie muses in The Belly of the Atlantic, “I’m all in favor of globalization, because it turns out things with no identity, no soul, too diluted to stir the least emotion in us.” (Diome, pp. 20). Above all, there is a constant scrabbling together of resources for the next month, the expenses of family, the cost of fuel for the pirogue balanced against increasingly poor catches.

The Atlantic route has for the past few years been policed by the Spanish coast guard, working in cooperation with Senegal’s government. Those who are picked up on the high seas are sent home.

The Senegalese, then, have actually had two routes: the 1,000 mile ocean voyage to the Canary Islands; or the increasingly dangerous trek across Central Africa to Libya and then across the Mediterranean. The news of the inhumane conditions of detention in Libya and crowded, unseaworthy vessels provided by traffickers have reached Senegal; in addition, the enforcement by the EU generally and Italy in particular resulted, by late 2018, in an increasing number of those who again choose the ocean (Reuters, December 3, 2018 ; see also European Commission Report, pp. 11-15, for an overview of Senegal’s total numbers).

Why go at all?

There are two major structural problems facing Senegal, both of them human-made. One is overfishing. In 2012, when La Pirogue was released, the newly elected government canceled the licenses given to giant trawlers, registered to Russia and China as well as other smaller nations, which were using satellite technology and overfishing the waters. Not only were the catches down, but the fish were taken elsewhere to be sold, rather than Senegal itself. The 52,000 artisanal fishermen in the country had threatened to take direct action themselves (The Guardian, May 4, 2012; see also Greenpeace.org, May 4, 2012). So the licenses were pulled, but the pirate trawlers are still there, having managed to get new licenses or just fishing illegally. And who will keep them out?

The other problem is climate change. The sea levels are rising, making low-lying coastal areas, further battered by rough and unpredictable storms, uninhabitable. Greater acidity in the oceans has damaged certain kinds of sea life, thus transforming entire ecosystems. The migration of fish toward the poles, as water has gotten warmer, has made them scarce in the waters they have traditionally populated. The ocean is able to absorb less carbon dioxide and thus plays a diminishing role in regulating temperature on land (edf.org; conservation.org). Another result of climate change, and the most visible one, is migration, along with the tendency to blame those who are taking this direct action to save themselves.

It’s only after finishing Anna Badkhen’s Fisherman’s Blues that one fully realizes the catastrophic climate change that is undermining the way of life she describes, so subtle and relentless are her observations. The lack of fish where there used to be fish. A certain kind of fish they used to catch, now gone. Chasing rumors that lots of fish have suddenly appeared off Gambia, where they no longer are, if they ever were. The traditional culture of leaving a fishing ground if another boat is already there, now a matter of bitter disputes about who arrived first. The constant worries about money, overshadowing the birth of a new daughter. The news that oil rigs will soon be sixty miles off the coast, to exploit rich fields (no one seems to see this as any benefit to the Senegalese, because it won’t be). A recently and carefully rebuilt nineteenth century Christian chapel that will inevitably, and probably soon, be washed out to sea. The discovery of a body on the shore–not a murder, but rather a gravesite desecrated by a heavy wave.

Badkhen, a journalist and award winning nonfiction writer, based herself in Joal, Senegal, at the southern end of the Petite Côte. She talks her way onto a number of different local fishing boats, but writes most about the Sakhari Souaré, the pirogue owned by Ndongo Souaré, and about his extended family.

On one occasion she is aboard when the Sakhari Souari spots a school near a decades-old wreck:

The crew bend as one and start ladling the net out to sea. Yard by nylon yard, arms straight, palms facing out, they push the mesh overboard in synchronous rapid motion. Coaxing it out. Offering it to the ocean as an oblation . . .

Faster, faster. Work like men, work like men.

The last of the net plashes into the water. The instant its four-fluke grapnel anchor slips out of the pirogue after it and sinks, the crew grab a hammer–a knife–an awl–a loose wooden burden board–and begin to whack the pirogue. They pummel the gunwales and the ceiling hard, and they stomp on the thwarts with bare feet in a ferocious and ancient abandon . . . Amid this unholy sacrament the skinny boy Maguette swiftly strips down to cotton boxers and a red gris-gris belt weighed down with leather amulet pouches and somersaults into the spiral heart of the gill net right by the shipwreck and there begins to splash madly in the green boil of the sea to scare the disoriented and deafened fish into his father’s net. . . . In the bow, the Sakhari Souaré’s first mate, one of Ndongo’s half brothers, drops a board into the hold, reaches inside the waterproof pouch around his net, pulls out a cellphone, turns his back to the wreck, and snaps a selfie (p. 14).

In the end Ndongo and his crew get only about two dozen fish that are worth selling. Still, even in recent memory, some speak of extraordinary catches so rich that they have to call extra boats to help them get the fish to shore, one such event just the previous year (p. 48).

“What kind of knowledge,” she wonders, “does it take to depend on a resource so seemingly bottomless yet so palpably expended, to exacerbate its decimation each day you honor family tradition? And what is the protection against the crushing void of the ever encroaching tide? Or against mostly illegal foreign ships that come in so close that on a clear night you can see from the beach their searchlights: eerie winks of a modern, mechanized organism that employs half a million people worldwide, vacuums the ocean empty, drowns out the ancient shanties of men who stubbornly chase fish in wooden boats? (p. 44).

It is a question that all of us will be facing. In different ways. In different places. At different times.

But soon.

================================================================

Header image from Shutterstock.com.

Additional source:

Fat Diome, The Belly of the Atlantic trans. by Lulu Norman and Ros Schwartz (London, 2006; originally published as Le Ventre de l’Atlantique, Paris, 2003).